Tavaine Whyte remembers the sound of bullets whizzing past his window late at night.

Tavaine Whyte remembers the sound of bullets whizzing past his window late at night.

Whyte, a freshman African American studies major, grew up next to the housing projects in Brooklyn. Living near the projects exposed him to violent situations and required him to always be alert of his surroundings.

“I remember the fights that gangs would have in my local park (H park) and the times I had to run when the shots rang,” he said in an email. “I remember walking the streets of my neighborhood at age 9 wondering if I would live to see 18.”

For Whyte, school was not always a haven from than the streets.

Students from rival middle schools often fought each other, he said. As a result, some of Whyte’s friends were hospitalized and one of his friends died.

But those aren’t Whyte’s only memories.

“The one time that I can say all the schools and students connected was while vibing over hip-hop,” he said. “I remember making drum patterns on school desks rapping the lyrics to “Forever” by Drake. Those were some of the best times of middle school.”

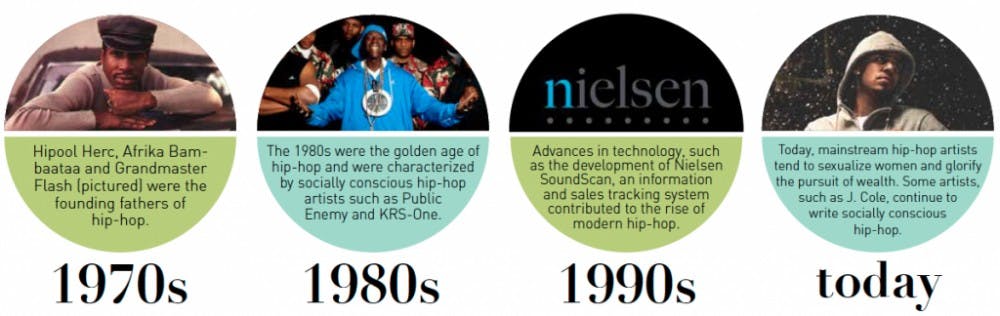

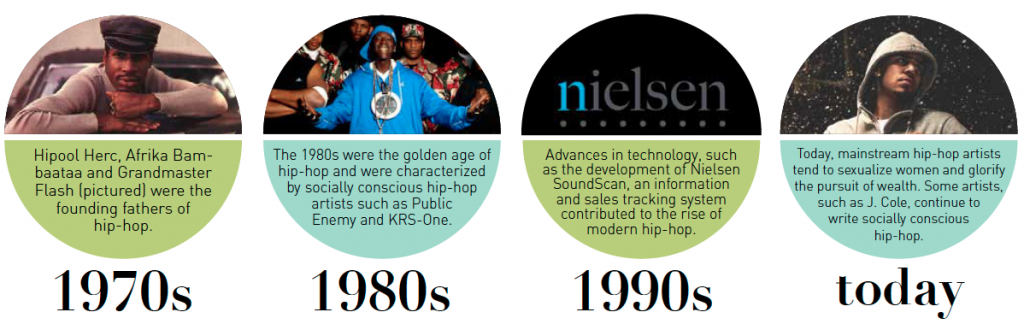

Youth across the United States embraced hip-hop in the 1970s as a social response to systemic problems such as crime, poverty, street violence and gentrification, according to Kushal Bhardwaj, known as ‘Dr. B,’ an academic adviser, athletics instructor and professor of UB’s Hip-Hop and Social Issues class. Hip-hop culture, which includes DJs, MCs, rap music and graffiti art, has evolved in response to changes in cultural ideals and technology. Today, Whyte and students across UB continue to identify with both original and modern-day hip-hop culture.

Hip-hop’s disciples

Hip-hop is integral to Whyte’s lifestyle and influences the way he acts, dresses and speaks.

“I hear the voices of my peers on some of these songs and the frustration is something that I relate to heavily,” he said. “Hip-Hop made me.”

Whyte is inspired by hip-hop lyrics, his favorite being: “It drops deep as it does in my breath / I never sleep / ’cause sleep is the cousin of death” from Nas’ song, “N.Y. State of Mind.”

This line has multiple meanings for Whyte. For example, Whyte can relate because he remembers how it was risky to fall asleep and not be vigilant while living in the ghetto. He also said this line could represent the life of drug dealers who often need to sacrifice many hours of sleep to make a living.

“The fact that Nas wrote this line at age 19 astounds me to this very day,” Whyte said. “[He was] a young black teen growing up in the worst situation, telling stories of those who never have their screams answered.”

People do not have to grow up in the ghetto to connect with hip-hop, according to Christina Dunn, a sophomore sociology major and vice president of Black Student Union, a Student Association club. Dunn said she identifies with hip-hop because she struggles to pay for college.

“My parents didn’t go to college,” she said. “Sometimes they’re suffering at home while they’re putting me in college.”

Dunn’s favorite quote from a hip-hop song is, “They say anything’s possible / You gotta dream like you never seen obstacles” from J. Cole’s “The Autograph.”

Noelle Nesbitt, a senior biomedical engineering major and president of Black Student Union, said minority students identify with hip-hop not only because paying for college is difficult, but also because they are often first-generation college students and are learning how to navigate interactions in a multi-racial school.

Her favorite line from hip-hop music is, “You can buy your way out of jail, but you can’t buy freedom,” from Kanye West’s “All Falls Down.”

The Bronx salad bowl

During the 1970s, the sociopolitical environment in New York City created the perfect “petri dish” for the creation of hip-hop, Bhardwaj said. New York City was not simply a melting pot where people sacrificed their individuality for the group. It was a salad bowl.

“You’re a carrot, I’m a tomato and you’re celery. We’re all in the same bowl,” he said.

Under the leadership of Afrika Bambaataa, Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash, hip-hop emerged in the South Bronx in the 1970s as a way for black youth to connect with each other and express the challenges of living in a discordant society.

In particular, Afrika Bambaataa emphasized how hip-hop served as a way to create unity.

“He was the Prometheus of hip-hop,” Bhardwaj said. “He taught us the fire, and it was around that communal fire that we built the culture.”

Whyte agrees and said hip-hop was a way for young, black youth to develop solidarity.

“A young black youth in the mid ’80s could go to a local party where a DJ would start mixing a break beat together with a rusty record player and feel a sense of community with those around him,” Whyte said. “The sense of togetherness that hip-hop gave was beautiful to see, considering that the art was formed from the creativity of those with little to no money to their name.”

Bhardwaj and Nesbitt agree that people often misperceive hip-hop as a genre solely created and consumed by young, black men. Although young, black men still dominate the genre, people from countries such as Germany and Japan are embracing and rearticulating hip hop, Bhardwaj said.

And if it weren’t universal, hip-hop wouldn’t be music, according to Nesbitt.

“The more the merrier,” she said. “If you like what I like, we can get along.”

This mentality lies at the heart of hip-hop’s predecessor: Jazz.

Peter Clavin, a Ph.D. American studies instructor, said jazz was the first mass-produced counterculture and brought whites and blacks together during the Roaring ’20s.

“Jazz was this incredible moment of syncretism,” Clavin said. “They were occupying the same space on a Friday night, which was nothing short of revolutionary.”

Jazz became mainstream in the 1930s and became counterculture again in the 1950s when the Beat poet movement associated it with drugs and sex, Clavin said in an email.

By the early 1970s, hip-hop replaced jazz and became the primary countercultural force in the United States, Clavin said.

Activism, gangster rap and the fall of turntables

Chuck D., the founder of Public Enemy, referred to rap as “Black America’s CNN.” Without N.W.A. and West Coast hip-hop, he said he would not have known what life was like in the streets of Los Angeles.

Similarly, Jesse Jackson, a civil rights activist, believed rappers turned “a mess into a message,” according to Bhardwaj.

Today, the opposite is true and rappers are paid more to say less, he said.

During the 1980s, revolutionary groups such as Public Enemy and KRS-One based their music on pro-black consciousness and made the 1980s the golden age of hip-hop, according to Bhardwaj.

“Those acts made it cool to wear African medallions instead of the big gold chains,” he said.

Although hip-hop originally aimed to expose and fight social inequality, modern hip-hop often glorifies wealth and objectifies women, Clavin said.

This shift in style began in the 1990s when Mike Fine and Mike Shalett developed Nielsen SoundScan – a computerized system used to track sales in the music industry.

Data from SoundScan revealed that consumers bought twice as many albums from N.W.A., a gangster rap group, than from Public Enemy, a more socially conscious rap group.

To maximize profit, record executives chose to focus on selling a more “debased” form of hip-hop instead of selling socially conscious hip-hop, Clavin said. Their motivation to earn money caused them to neglect the consequences of popularizing gangster rap.

“An arbitrary piece of paper [became] more valuable than a human life,” he said.

Bhardwaj said hip-hop is currently at risk for losing its core functional component – the DJ. Serato software – a modern-day technology DJs use to play music on their laptops – is replacing the traditional practice of using turntables and vinyl records.

“It reproduces the sound, but the discipline of the old, actual physical instrument is getting lost,” Bhardwaj said.

Unlike original hip-hop, modern-day hip-hop does not tell a story, according to Nesbitt.

“I don’t listen to the lyrics,” she said. “I listen to the beat. You can’t really relate to [the lyrics] anymore.”

A caricature of society

Bhardwaj and Clavin agree that modern-day hip-hop is similar to minstrelsy – a form of 1830s American entertainment featuring white actors performing blackface and portraying blacks as primitive and ignorant. Today, mainstream rappers “put on the costume” of black stereotypes, according to Bhardwaj.

Paradoxically, many people who criticize the themes of modern-day hip-hop – such as the emphasis on wealth and sexual objectification of women – do not realize that these themes not only dominate mainstream hip-hop, but also characterize American society, Clavin said.

Clavin said the lyrics illustrate themes that apply across American society.

“Hip-hop’s problems are society’s problems,” he said.

Although gangster hip-hop dominates the music industry, socially conscious hip-hop still exists, Dunn said. For example, she listens to J. Cole recent song “Be Free,” which is based on the events surrounding Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri.

“There’s socially conscious hip-hop out there,” she said. “It’s just not played on the radio.”

Today’s fight

As a cultural phenomenon, hip-hop will inevitably stray from its roots and continue to evolve and migrate across the globe, according to Bhardwaj.

Rearticulating art is important, but it’s also essential to stay in touch with its cultural roots, he said.

“The fire of hip-hop continues to burn,” Bhardwaj said. “[But] people are looking at the smoke and not recognizing the fire.”

The issues of the 1970s – such as gun violence and segregation – continue to exist today, according to Dunn.

J. Cole recognized these issues through hip-hop when he visited Ferguson and wrote a song in tribute of Brown’s death, Dunn said.

Dunn said that Cole empathized with Brown because black males across America are equally vulnerable to discrimination, regardless of their economic status.

“Even though he’s a celebrity, he’s still a black man,” she said.

People in Buffalo may also identify with the problems hip-hop culture addresses, Clavin said. He said the suburbs of Buffalo have a high concentration of white people and that the city invests less in areas dominated by black people such as the West Side and East Side.

Hip-hop can influence policy-making and bring these problems to the forefront of our discussions, Bhardwaj said.

“To live hip-hop is to not just listen to hip-hop music but to let the culture permeate the way you approach everything in your life,” he said. “It indeed is a shared consciousness that transverses cultures, ethnicities, races and languages.”

email: features@ubspectrum.com