UB students want fake IDs and they pay hundreds to get them.

Joseph Clay* knows.

He used to sell them.

Clay started an illegal business -- one that could have landed him in prison -- during his first semester at UB.

For almost three years, Clay sold hundreds of fake IDs each month to UB students.

“I couldn’t even tell you how many fake IDs I have sold,” Clay said. “I just did it for so long and in such big waves.”

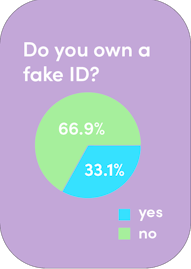

In a Spectrum survey, 33% of 273 UB students said they have used a fake ID in order to get into bars and clubs or purchase alcohol. Some bought fakes from a dealer or website and others borrowed real IDs from friends over 21. In The Spectrum’s survey, students said they have spent up to $250 on a single fake ID. The average cost was $75.

Proof of identity fraud can lead to criminal charges, however most students get off with a warning because of how widespread fakes are, according to UPD Deputy Chief Joshua Sticht.

Nearly 70% of UB students are undergraduates who won’t turn 21 until their junior or senior years of college. Having a fake ID can be the difference between staying home on a Friday night or being with friends at bars or clubs.

The business of fakes

Clay started selling fake IDs to his classmates when he was a junior in high school. He would buy them from online distributors for $50 per ID and then sell them for more.

“People were offering to pay a hundred [dollars] or more for two IDs.”

Online distributors would cut down the price of the individual fakes for bigger orders. The bigger the order, the bigger the profit Clay would make.

“I turned it into a little business,” Clay said.

When Clay started at UB in 2016, he said his business doubled, tripled and quadrupled.

“The main benefit was coming here,” Clay said. “People knew my name and knew that I could [sell them fakes]. So roommates starting talking, then frats, so that’s when it really took off.”

Clay said the majority of his sales took place in the University Heights or other off-campus housing locations like University Village Sweethome.

He said the demand was “huge” and he would pay or give someone a free fake if they found other customers for him.

The biggest orders came from fraternities, sororities and dorm floors, according to Clay.

“If people got their IDs taken, I would offer them a deal that they would get their second order cheaper. It was just little things to keep people coming,” Clay said.

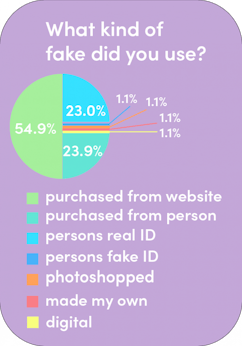

Clay said most of the fakes he sold were Delaware and Ohio licenses. New York licenses were the most in-demand, but authentic-looking New York fakes were harder to find.

“You could get them from China, but they would take forever to ship here and could get seized from the border, plus they were usually s––t quality,” Clay said.

Clay usually ordered the fakes from within the U.S., using a secure internet program called Pretty Good Privacy to encrypt his messages and sensitive information, such as the number of IDs and the names of the people buying the fakes.

Once he developed a secure system for selling fake IDs, he decided that he could do the same with drugs.

Clay found sources online to buy everything from marijuana to cocaine and MDMA.

He went from being a fake ID card dealer to a drug dealer.

Clay, a commuter student, initially received the envelopes of fakes and drugs at his parents’ home. He eventually started paying people to receive his packages for him when orders became consistent.

Clay said he didn’t worry that his packages could be confiscated.

“There’s a low chance with ID orders and even with drugs, that an [envelope] coming from inside the U.S. would get flagged,” Clay said. “The postal service is so poorly funded and understaffed.”

But there were moments of intense anxiety, Clay said. There were a few instances where police stopped him while on a drug or ID run.

“And all of a sudden you have fill-in-the-blank felonies sitting in your car, and the heart attack you get when you get pulled over with that kind of stuff.”

During his heaviest dealing, Clay was failing his UB courses. He dropped out of UB in 2017, but he continued to use the campus as a network to sell goods and his business continued to thrive. He ordered packs of fakes every couple weeks for 20 to 50 people, he said.

Not all students looking to buy a fake rely on people like Clay. Some students order fakes directly online themselves.

Rachel Dudley*, a junior civil engineering major, bought her first set of fake IDs in high school to buy alcohol. Dudley said she used the website “ID Gods” to buy two Pennsylvania driver’s licenses for $80.

The website’s source distributor is located in China. Dudley said the IDs were sent disguised as a package of chopsticks to get past international customs.

Her fake IDs were registered and cleared when bouncers and cashiers scanned them, according to Dudley.

“People could tell if it was a fake sometimes,” Dudley said. “They get suspicious if it’s an out-of-state license I think.”

Dudley said corporate-owned stores like Tops or Wegmans wouldn’t accept the fakes, but smaller, privately owned liquor stores would sell to her. Dudley had trouble using it at some bars as well. When she tried using it to get into Cole’s on Elmwood, the bouncer knew it was fake. He told her he couldn’t give it back to her and kept it.

A Buffalo Police officer took her other fake in the University Heights.

Dudley said she was walking into a house party when the officer stopped her and her friends because they had open bottles. The officer confiscated her wallet and seized her fake ID. He ticketed the girls for having open liquor bottles, but not for underage drinking or having a fake ID.

“He knew it was in my [wallet],” Dudley said. “And he was like, ‘Oh, Pennsylvania, I’m gonna keep this.’”

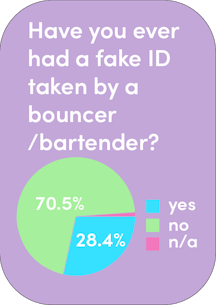

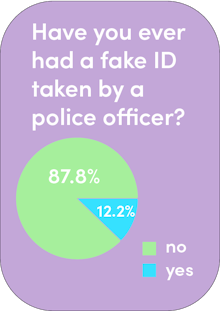

In The Spectrum’s survey, 12% of students said they have had their fake ID confiscated by a police officer and 27% said they have had it seized by a bartender, bouncer or cashier at a liquor store.

She tried using a New York State fake from “ID Gods” after her Pennsylvania fakes were taken. Those IDs did not scan and were taken the first time she tried using them, she said

Dudley said she tried using it at the Steer Restaurant and the bartender told her that he couldn’t serve her with that ID.

“I remember the bartender at Steer, he was like, ‘I can’t even work with this, get a better ID,’” Dudley said. In all, she said she spent $160 on fakes over the years.

Now Dudley uses a real driver's license she borrows from an older relative to get into bars.

“That one works everywhere because it’s real,” Dudley said. “And I think it kind of looks like me.”

Carrissa Mauro*, a junior psychology major, said she bought a fake Ohio driver’s license from a mutual friend in high school, which she continued to use in college. Mauro said at first having a fake ID was “a rush of adrenaline.”

“When I was 17, it felt like a new, fun challenge. Could I get into these bars and would they believe it?” Mauro said. “It was exciting having a fake ID and having people be like, ‘Wow, yours is so real looking.’”

But Mauro said getting her fake taken at a bar felt like one of the worst things that could happen because it meant getting “left behind” by all her friends. Trying to get past the bouncers became a huge anxiety.

“It was a constant scheme trying to get into bars,” Mauro said.

Mauro also sometimes used the “pass back” method with her friends. When she was visiting Fredonia this past fall and attempting to go to the bars, she realized she left her ID at home. Her friends got into the bar with their fakes, then pretended to step out for a phone call and hand their fake to her to use.

“Five minutes later, I was in the bar,” Mauro said. “Which just proves that some people don’t care even if they know it’s a fake.”

Mauro studied abroad in London this spring, where she has been able to drink legally.

“Being 20 here is so much different,” Mauro said. “The drinking age is 18 [in England], so you are treated as an adult, you can do things. Coming back here and having to use a fake again feels childish.”

Cracking down on fakes

Many states, including New York, have boosted the technology of real IDs with holograms, magnetic strips and bar codes, making the process to make realistic fake IDs more complicated and expensive.

Sticht said the repercussions of being found with a fake ID can vary, but UPD officers will usually give students warnings if they find out they have a fake.

Deputy Chief Joshua Sticht shows the fakes confiscated from students over the years. UPD keeps a set in the department to train new officers in deciphering fraudulent forms of identity.

Physically altering a real license by changing the date of birth is equivalent to a speeding ticket violation, while falsifying or forging a driver's license can lead to a class B misdemeanor, according to Sticht.

“You can go to jail up to a year for that,” Sticht said. “Though most college students don’t get that far just for purchasing alcohol or trying to get into bars.”

New York State Gov. Andrew Cuomo has been pushing for a crackdown on underage drinking.

In 2018, Cuomo began “Operation Prevent” -- designated times when authorities planned fake ID sweeps at bars and concert venues. People who were caught using fraudulent IDs to get into these venues or buy alcohol were arrested and charged with misdemeanors. Cuomo announced on Feb. 1 that a record number of minors had been arrested for possession of a fake ID. In 2018, New York State made 922 arrests for possession of a fake, 394 of which took place in Western New York.

Twenty-four were arrested and charged with misdemeanors at The Steer Restaurant and Main Place, according to Cuomo’s announcement. Buffalo accounted for 6% of the total “Operation Prevent”arrests in Western New York in 2018.

Department of Motor Vehicle investigators targeted Darien Lake concerts over the summer, according to The Daily News in Batavia. The outdoor concert series, which runs from May to August, accounted for 108 of the Western New York arrest numbers. Twenty-four were arrested at the Post Malone performance on May 26 and 19 were arrested at Kendrick Lamar's concert a week later.

Jeff Martz, the owner of the Steer Restaurant, said his employees must go through mandatory training through the state so they can determine what a real ID looks like.

“There’s a New York State security course that all security take,” Martz said. “We do the best we can, I’m sure some [fakes] get through.”

Martz said his employees won’t let someone in the bar if they present a fake, but they do not take the ID from the person.

“We’re not supposed to take them,” Martz said.

Sticht said bars and liquor stores are supposed to call the police or the State Liquor Authority when someone attempts to use a fake.

When UPD seizes a fake, officers sometimes discard it by shredding it, Sticht said. They keep a number of fakes in custody for training new officers on how to determine a legitimate driver’s license.

If the fake “looks like someone has put a lot of effort into making it” UPD will hand it over to the Department of Motor Vehicles Criminal Investigations Division so they can use it to find out more about the distributors, according to Sticht.

Sticht said bouncers at bars are caught in a difficult situation when a person under 21 presents them with a fake. If that individual were to end up in “any kind of accident afterwards, then the bouncer or bartender could be liable.”

“They can't let this person go into their bar and drink with this fake ID. But if they let that person go and that person then gets into another bar and drinks and does something wrong, gets into an accident and hurts somebody, that bouncer is potentially on the hook civilly,” Sticht said.

People like Clay who sell IDs can land in serious legal trouble also. In 2011, two students were arrested for making and selling IDs to other students at the University of Georgia and were sentenced to three months in prison with $6,500 in fines.

Clay recently quit all fake ID and drug operations and re-enrolled this semester to finish his undergrad at UB.

“I was in the dark place when I started doing that,” Clay said. “And then it just kind of turned into a business to the point where I was too comfortable doing it.”

He currently has a 4.0 GPA and is relieved to no longer have to worry about getting caught.

“I don’t think I ever should have been involved in the scene in the first place,” Clay said. “I just focused on the business part of it and got used to everything else.”

Clay said the thrill of dealing fueled him to take risks that he didn’t know he was capable of and the cash flow was too distracting.

“It was like an addiction,” Clay said. “Like any addiction, it fuels you to keep going for unhealthy reasons.”

*Names have been changed for anonymity.

Isabella Nurt is the assistant features editor and can be reached at Isabella.Nurt@ubspectrum.com and on Twitter @Nurt_Spectrum.

Isabella Nurt is a junior film production major. She is keen to get off campus and cover underground topics in the greater Buffalo area.