DeShawn Henry wants to make a difference in the world.

He started with a tall-wooden frame with plastic sheeting sitting on top. A Styrofoam box painted black creates a focal point for sunlight, suspended in the center of the frame. Weights are placed around the plastic so it is held taut and water is given space to evenly distribute, creating a spherical lens, similar to a contact lens.

Henry, a sophomore civil engineering major, and James Jenson, a professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering, spent this summer researching effective and inexpensive ways to disinfect water.

A water lens using solar disinfection was their solution.

Jenson and Henry used a water lens to test how much safe drinking water the sun’s heat – which eliminates bacteria and disinfects the water – could produce. Using wood and plastic, Jenson and Henry were able to consistently disinfect water using the sun’s energy – all for the price of Saran wrap.

Through the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAP), Henry, along with 11 other students, had the opportunity to work on research projects within the university. The eight-week intensive program allowed each intern to work closely with a faculty adviser as a mentor. The project required each intern to attend team-building seminars twice a week.

Jenson believes the idea of using the sun’s energy to heat water is ancient, but building a device to harvest the sun’s energy came from the Internet.

“I looked it up and there was a YouTube video of someone who built a gigantic [lens] in their backyard and used it to burn wood,” Jenson said. “And so I said, if you can burn wood with this, you should be able to use it to treat drinking water.”

Jenson brought the idea of creating a water lens to Alex Valencia, a UB alumnus, almost four years ago. Together, Jenson and Valencia laid the initial groundwork – building the frame and analyzing how the size of the frame affects its efficiency.

Henry worked with three types of plastic materials – painters’ drop-cloth, saran wrap and the plastic used to wrap shipping crates. Jenson even suggested using the plastic wrap from UB’s food services.

Once the water’s temperature reaches 135 to 150 degrees Fahrenheit, bacteria and bugs are killed, making the water safe to drink.

Much of the research involved in this project isn’t on the lens itself but on the mathematics behind it.

“Now, you might be thinking, this is so simple, a child can throw some water up there, but [Henry’s] work got really complicated because the shape of the lens changes depending on whether the plastic is thick or thin,” Jenson said.

The type of plastic used affected how much water the lens can hold and how much water could be disinfected.

One of Jenson’s main objectives is for the lens to be made in the cheapest way possible. The civil and environmental engineering department is researching other materials that can be used to filter and purify water through the solar lens project as well as other water purifying projects.

“Our whole point is empowerment,” Jenson said. “People should be able to treat their own water without having to buy things.”

He suggests people turn to their backyards to find materials – even use their houses as the basis for the lens. The only material they’d have to find would be the plastic.

For the water lens to be effective, however, the weather needs to be clear and warm, which makes the lens’ use most feasible in the equatorial regions of the world.

But not in Buffalo, according to Jenson, because the lens would often succumb to the weather by falling over or tearing due to wind and inconsistent sunshine.

Jenson said the best uses of the lens would be in the case of an emergency, like an earthquake or typhoon, where it may be difficult to find clean water. Because the lens is so simple and inexpensive to build, using it in the event of a natural disaster would bring clean water to a large amount of people quickly.

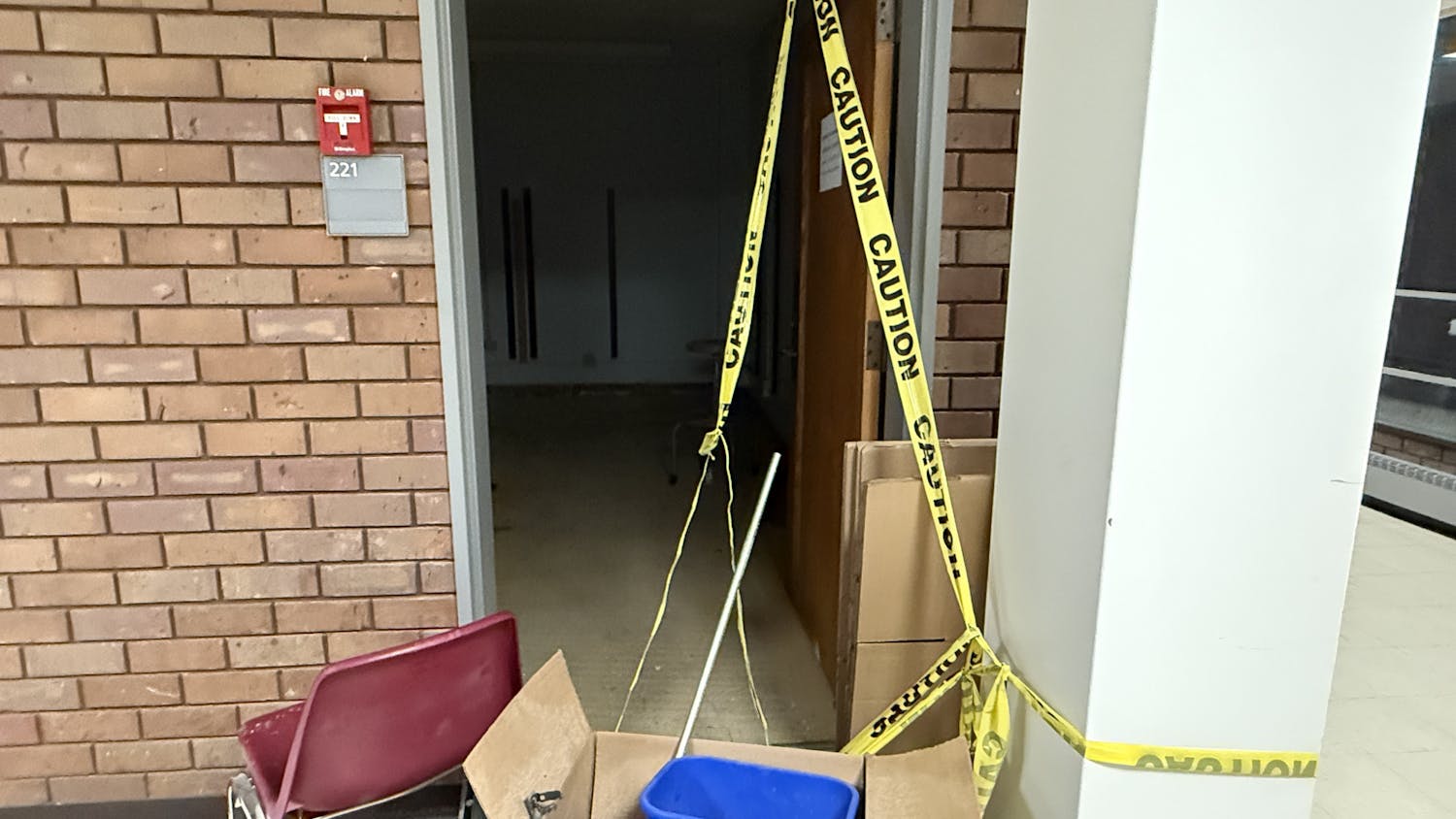

Research on the lens has been halted because the incoming cold weather makes it harder to keep and maintain heat. But this does not mean that research on different types of water filtration systems has been stopped, too.

This year, the department has tested natural plant material, fabric filtration and ceramic water filters through clay pots made of rice husks as a way to filter water.

“It’s one of the most ubiquitous materials in the world because so many people use rice and throw away the rice husks, so we’re making clay pots out of those,” Jenson said.

Henry said if a person has the materials to build the lens, then they have the ability to save their families and their communities.

email: news@ubspectrum.com