All over the world, cities have experienced the problem of sinking buildings. Venice. Toronto. Mexico City.

The latest: Amherst.

Over the past year, an increasing number of Amherst residents filed complaints citing foundation damage ranging from buckling to cracking, all due to this "sinking" effect.

However, while UB professors and students' homes have sustained damage, the campus itself is safe on account of careful construction, UB geologists say.

Darlene Torbenson and her son Greg, a junior electrical engineering major at UB, were two such residents to witness the unexpected deterioration of their house on Dappled Drive in East Amherst.

In 1997, the Torbenson home began to display signs of differential settlement, a process in which portions of the ground beneath a home settle, causing parts of the house to rise and other parts to sink. According to Darlene Torbenson, who is also a member of an Army Corps project team looking for the cause of this shifting, it takes from eight to 20 years before effects become noticeable.

Now, the 23-year-old home's foundation has essentially broken apart and no longer supports the house. Since the damage became apparent, Torbenson said that the cost of repairs is up to about $130,000.

Basement repair alone is estimated at $66,000, and that's not taking into account the damage done to drywall, doors, and windows, she said.

According to her son, who now lives on campus, it was distressing to live at home and watch this happen.

"One day, the foundation basically started to break and the ceiling was separating from the walls. It was gruesome," he said. "It's frightening to actually see the basement - it looks like a bomb went off or there was an earthquake."

Keith Bryan, a junior political science major, endured a similar experience. His family's Dappled Drive home also sustained considerable damage, including cracks that span from the basement straight through the attic.

"You feel powerless, because there's nothing you can do about it," said Bryan. "I feel even more powerless than my parents because they have to pay for college as well as the damages. This was not budgeted into my parents' future plans at all."

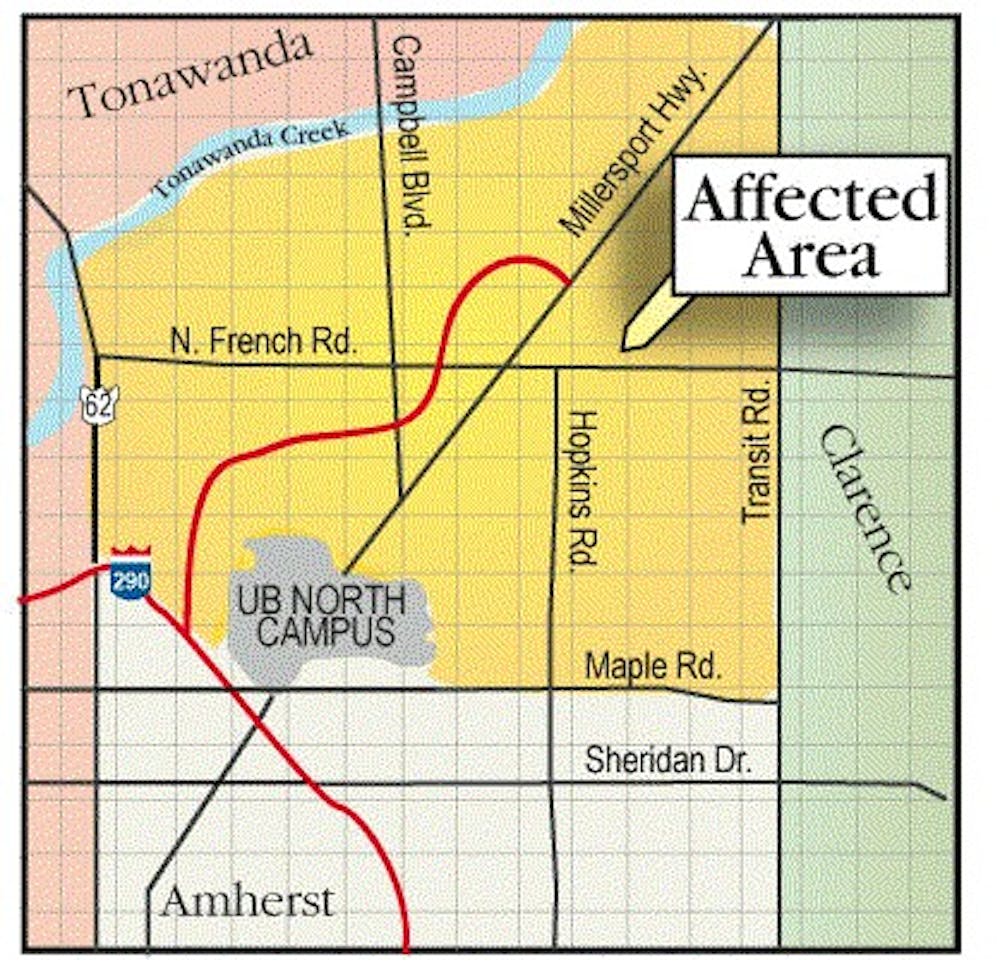

According to Amherst Town Building Commissioner Thomas Ketchum, the majority of the problems are north of Maple Road.

Ketchum said North Campus does have the same soil composition as those areas, and the average age of the structurally damaged homes is 34 years - a number that lines up with the construction of several North Campus buildings.

Yet UB should be able to withstand this kind of earth movement, according to Stuart Chen, an associate professor of civil engineering at UB.

Chen, whose home also suffered substantial damage due to sinking, explained that commercial building codes would have required soil investigation before construction. Furthermore, steel reinforcement bars, known as "rebar," were required to be placed in the foundations of the buildings, stipulations that were not a part of the residential building code at the time the affected houses were built.

"I would be surprised if (the differential settlement) affected the academic buildings at UB, because they would have rebar in the foundations," said Chen. "If the houses were built like the buildings at UB, we would be seeing fewer problems. Even though they're built on the same soil, the UB buildings are better constructed."

Matthew Becker, an assistant professor of geology at UB, added that since the majority of UB structures are large buildings, their supports would go all the way down to the bedrock layer, and this would altogether rule out the possibility of sinking.

"I have no expectation of sinking except for maybe the parking lots," said Becker.

There has been speculation as to the cause of the differential settlement in Amherst, but no conclusions have been reached, according to Ketchum.

"There are a number of possible factors that could have caused this - soils; the effect of trees, which can draw moisture out of soil causing a settling effect; a slope in the property that causes water to pool around the foundation; structure strength of the concrete; even drainage problems could be causing this," said Ketchum.

"The dominant theory at this time, though, is that there is a soft clay layer beneath the affected homes," said Ketchum. "Over time this layer has dried out, causing it to shrink, which would then create this sinking effect."

While this quandary has become a mounting concern for Amherst residents, Ketchum wants to stress that this problem affects only two percent of the parcels in Amherst.

Torbenson said the first Army Corps study investigating the source of these problems was published in The Buffalo News on Feb. 17.

According to Torbenson, soil stability is a major factor. Since most of the affected properties are built on flood plains and former wetlands, the land is experiencing what is known as a dewatering process, where water is drained from the soil and away from the home. This process is meant to protect the home but has had negative effects on the soil.

This dewatering process and the weak nature of the soil are the key factors in the damage that has been done to these houses, according to Torbenson. She said the Army Corps expects to have a complete study by the end of 2004.

Torbenson said that the Town of Amherst knew this information in 1972, yet it didn't take the data into consideration before developing the area.

"The damage could have been avoided with more planning and testing," said Torbenson.