Laura Aguilera’s depression came on slowly.

She started waking up feeling very tired her sophomore year. This unshakeable fatigue gave way to a diminishing appetite and a lack of motivation. She wasn’t interested in anything and wanted to sleep all the time.

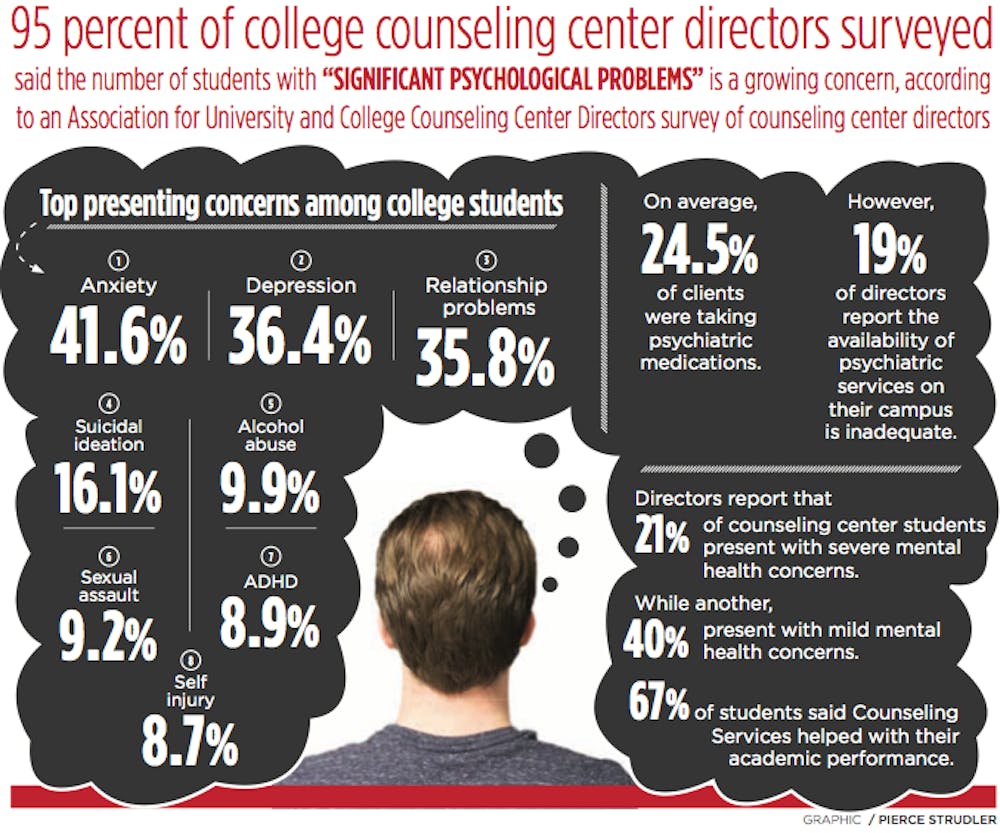

Ninety-five percent of college counseling center directors surveyed said the number of students with “significant psychological problems” is a growing concern, according to an Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors survey of counseling center directors. Almost one third of all college students report having felt so depressed they had trouble functioning, according to Active Minds, a nonprofit dedicated to raising mental health awareness among college students. Active Minds states that mental health issues in the college student population, such as depression, anxiety and eating disorders, are associated with lower grade-point averages and higher probability of dropping out of college.

Sharon Mitchell, director of UB’s Counseling Center, believes it’s hard to single out just one factor that leads to high rates of mental illness among college students. She said common triggers include financial problems, cultural shock, family problems, physical illness, lack of adequate academic preparation and a lack of a sense of community or belonging.

Role of assault in mental illness among college students

The summer after Aguilera’s freshman year, she experienced a sexual assault at a party. She feels that experience played a large role in triggering her depressive episode.

“It relates to being a student because a lot of students experience sexual violence and it affects their mental health,” the senior global gender studies major said.

Sexual violence in the college environment can be confusing as it often perpetrated by someone that the victim knows, according to Mitchell.

“This reality can make it difficult to make sense of what happened or to even accurately label the experience as sexual assault,” Mitchell said.

Senior Adrian Villanueva* feels her mental health took a turn for the worse in late January of her freshman year after the person she was dating sexually assaulted her when she tried to break up with him.

“After saying no a lot, I realized it was just going to happen,” Villanueva said. “I got out of there as soon as I could and I was able to break it off after I got out of physical space with them.”

Villanueva never reported the assault. It took her a long time to even understand that what happened to her was assault. And she blamed herself for what happened.

“I thought, ‘oh you put yourself in that situation. If you hadn’t been seeing him it wouldn’t have happened,’” Villanueva said.

Mitchell said this type of self-blaming and sense of shame is common.

“Assault leads to disruption in the person’s sense of safety, sense of their judgment, a tendency to self-blame and feelings of shame,” Mitchell said.

These feelings can lead to disruption in a student’s functioning, interpersonal relationships and academic performance.

After the assault, Villanueva started drinking. She didn’t drink at all during her first semester, but she started going to parties and drinking heavily after the assault.

“Social drinking is such an easy way to hide a problem,” Villanueva said. “Everyone thinks it’s okay because everyone is drinking.”

But soon her “weekends slipped into weekdays,” and Villanueva was drinking on school nights to quiet her thoughts.

“And that’s great until you stumble into bed at three in the morning and you still can’t sleep because of all you’re thinking about,” Villanueva said.

Painful memories of the assault and intense anxiety kept her wide awake at night. She stopped attending classes. Her grades started slipping from As to Ds. She would often forget to eat, which she said was very easy to do when she was in class all day.

“I think I went three days without eating at one point,” she said.

Villanueva finally realized something was seriously wrong when she started “going off with guys.”

“Before I entered college I had a purity ring. [...] I was still a virgin when I was with that person, but very much not so afterward,” Villanueva said.

She sought therapy from UB’s counseling services feeling that she needed to “fix herself” before she couldn’t anymore.

Therapy wasn’t a huge help at first, but Villanueva said that’s because she wasn’t addressing her assault, which she felt was the root of a lot of her problems. She still blamed herself and struggled to understand that what happened was, in fact, an assault.

But once she started processing and opening up about the assault, therapy helped her work through it.

“You can put yourself in a situation, but if you say no, that’s it. That’s clear as day,” Villanueva said. “But it takes you a while to get there to accept that and move past that for yourself.”

Depression, mania and psychosis

After Aguilera’s assault, she stopped attending class, lost her motivation and often stayed in bed all day.

She decided to seek help from a doctor from UB Health Services. He prescribed her an antidepressant and referred her to UB Counseling Services. Aguilera ended up leaving counseling after a few months because her therapist left.

After being on the antidepressant for a few months she decided to stop taking it because she was having suicidal thoughts.

Aguilera continued to struggle throughout her junior year and had to take incompletes during that spring semester. By the time senior year came around, she was still missing a lot of classes. She had to resign from several courses and sought help from a psychiatrist.

The psychiatrist put her on a medication that triggered her first manic episode. Aguilera did not sleep for days at a time, lost her appetite and felt extremely energized, saying it was “worse than the depression.”

The mania developed into psychosis. Aguilera locked herself in her room and stopped communicating with anyone for three days. She experienced delusions and felt paranoid, thinking people were out to get her. Most frighteningly, she experienced hallucinations that had her questioning what was real and what was not.

After her mom didn’t hear from her for three days, she came to check on her and ended up taking her to a hospital in Rochester.

Psychiatric hospitalization

When she was released from the hospital, the Conduct and Advocacy office contacted her to see what they could do to help her get back on track in her classes. But she wasn’t sure what they could do to help her at that point.

She became convinced her medication wasn’t helping so she stopped taking it and her psychosis came back. Her mom brought her back to the hospital, and this time she was admitted to the psychiatric unit.

“Being in the psych ward was one of the most terrifying experiences of my life,” she said. “I felt like I was in jail. And people in the hospital had been previously incarcerated said it was like the same thing as jail. … There’s a strict schedule, doctors come in and out. It was terrible.”

Aguilera’s hospital stay prevented her from graduating.

Academic withdrawal

Aguilera spent the summer focused on recovery and is now back taking one class so she has time to focus on her mental health. However, she has faced difficulty pursuing an academic withdrawal from the spring semester when she was in the hospital.

“The academic withdrawal process is stressful because you have to write an entire essay justifying why you want it,” Aguilera said. “You have to prove yourself and you shouldn’t have to prove that you’re suffering and need help.”

She had to explain her mental health struggles to her academic adviser, who had previously been condescending and dismissive to Aguilera regarding her mental health. She struggled to articulate what happened to her, unable to recall all of the fragmented, traumatizing details.

Coping and recovery

Aguilera said she has come to terms with the fact that she will be graduating a year later than she originally anticipated.

“I realized that I’ve been brainwashed into thinking I have to follow this certain time frame,” she said. “Recovery and healing isn’t a linear process, so there’s no way I’m going to fit into a perfect time frame that somebody else expects of me.”

Villanueva said she finally “woke up” when she received two Fs and lost her job. She dedicated the summer to getting better and putting her life back together. She took summer classes and attended weekly therapy sessions. Substance abuse stopped being an issue because her drug dealer was out of town.

Villanueva’s junior year was “much better” overall.

“I made sure I was socializing and actually getting interaction with people because sometimes I do isolate and not interact with people,” she said. “And then I just feel alone and miserable. I know once I’m with people I’ll feel better. And I was better with studying and being on top of my grades and stuff like that.”

She still suffered bouts of depression, but this time they only lasted two weeks at a time and only happened every once and awhile. She was able to “reign them in.”

Her substance use decreased because she didn’t have a reason to be using anything.

Villanueva said she got better at recognizing earlier when she was struggling.

Whenever Villanueva started to feel depressed, her therapist encouraged write down what was happening when her negative thoughts occurred.

“Intrusive thoughts were my biggest struggle,” Villanueva said. “These thoughts were like, ‘You’re a waste of space, you’re a f*ck up, you should slit your wrist.’ Those could be triggered by something like oversleeping and missing one

Villanueva finds distracting herself from these thoughts to be most helpful. But now instead of using alcohol, drugs or self harm, she does arts and crafts, a paint by number page, a coloring book or a puzzle.

Therapy also served as a huge help to Villanueva. She felt it was a space where she could be more open and honest about her feelings than she could be in her everyday life.

“The hardest part about depression is you feel like you have to act like everything’s okay,” she said. “You feel like you have to go to class and put on a smile and hang out with friends. You feel like you can’t talk to anyone. And then you’re just left with your own thoughts.”

Due to a demanding class schedule, Villanueva hasn’t been able to attend therapy this semester. She is in class or work from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. most days, so there simply isn’t time to go to therapy, even though she wishes she could go.

Aguilera said time has been a big factor in her recovery.

“Time, just allowing time to take place, time can be a good thing for recovery,” Aguilera said.

She has learned to be more patient with herself and has disability accommodations now. She finds meditation and drawing therapeutic.

Prevention

Aguilera thinks people should be more aware of the early warning signs of mental illness.

“I don’t think we’re taught how to keep an eye out for these kinds of things,” Aguilera said. “I don’t know exactly how we should go about that, but I think there should be some sort of training or program where students can learn how to keep an eye out for different mental illness symptoms.”

New York State is the first in the country to mandate mental health education be taught in high school health classes, according to Mitchell. This mandate will go into place next year. Mitchell believes this will go a long way to reducing stigma.

Mitchell also feels failure needs to be normalized.

“[Failure] should be viewed as an opportunity [for students] to learn something about themselves and their strengths,” Mitchell said. “Students can learn resilience and actually be even better as a result of overcoming or living through a setback.”

Finally, Mitchell believes showing compassion for others and having self-compassion rather than judgment helps reduce stigma around mental illness.

“This can be as simple as noticing changes in a person’s behavior or demeanor and saying, ‘Hey, you haven’t seemed like yourself lately. How are you doing?’” Mitchell said.

*Name has been changed to protect the student’s privacy

Maddy Fowler is the editorial editor and can be reached at maddy.fowler@ubspectrum.com