In 1998, commercial hip-hop was at a crossroads.

After the tragic murders of Tupac Shakur in 1996 and the Notorious B.I.G. in 1997, hip-hop was searching for its next two superstars.

The likes of Master P, Big Pun and Puff Daddy (more recently recognized as P. Diddy) dominated the radio, but none fully reached the level of cultural and commercial superstardom that Biggie and Tupac previously did.

While nobody could fill Tupac and Biggie’s enormous shoes, a pair of rappers were forced to take the baton and run with it.

Enter Biggie protegé Jay-Z and rugged Yonkers, NY battle rapper DMX.

In just a year, the two became hip-hop’s premier superstars, with one’s road to the top more likely than the other.

Jay-Z released his third studio album, “Vol. 2… Hard Knock Life,” in September 1998, launching him into mainstream superstardom. Having released two commercially and critically successful albums prior to “Vol. 2,” Jay-Z was hip-hop’s mainstream prodigy and was finally realizing his full potential as an international superstar.

From 1997 to ‘98, unsigned rapper DMX, born Earl Simmons in Mount Vernon, NY, was introduced to the mainstream hip-hop world with guest appearances on tracks by LL Cool J (“4, 3, 2, 1”), The Lox (“Money, Power & Respect”) and Mase (“24 Hrs. to Live” and “Take What’s Yours”). The battle rap underdog captured the ears of listeners with unmatched energy and a psychopathic fire fueled by a troubled past.

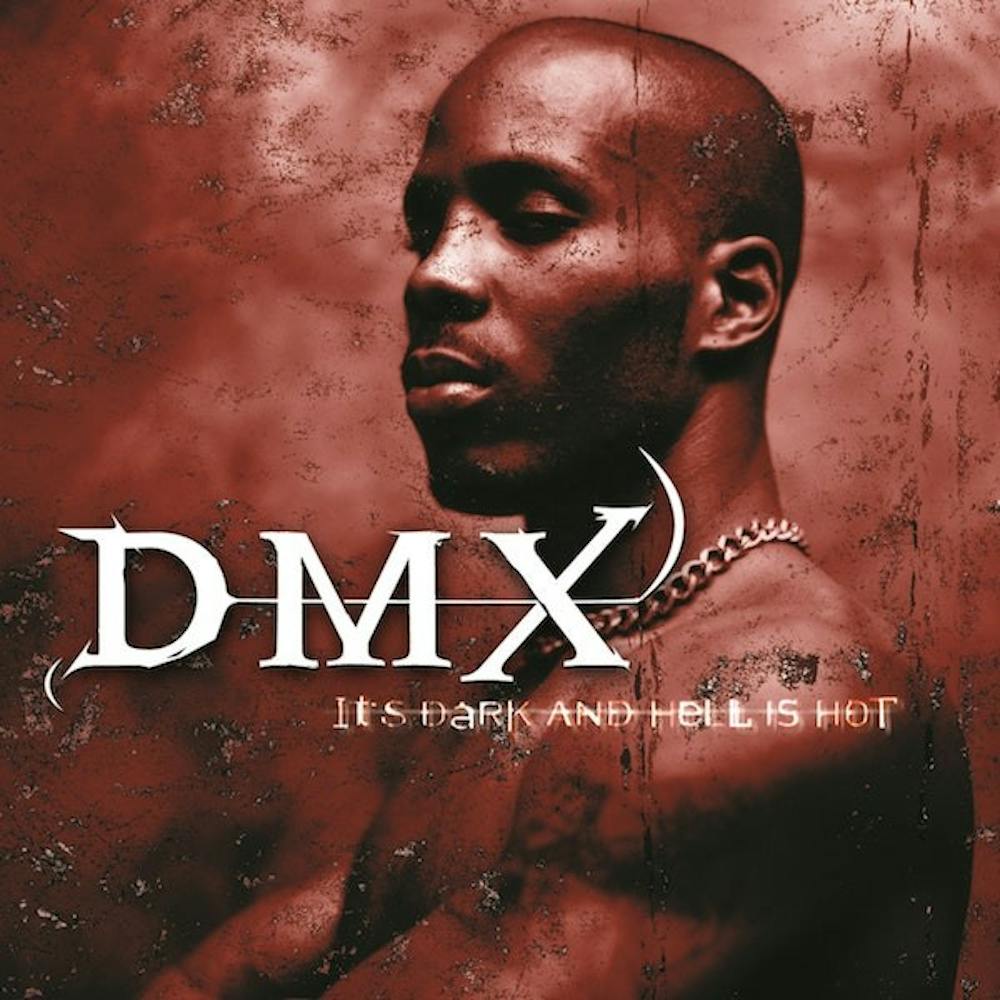

In 1998, a 27-year-old Simmons released his debut album, “It’s Dark and Hell is Hot.” Supported by singles “Get at Me Dog,” “Stop Being Greedy,” “Ruff Ryders Anthem” and “How’s It Goin’ Down,” the album saw immediate success and shot to No. 1 on the Billboard charts. With a charismatic start-and-stop delivery, an abrasive sound and anecdotal stories of emotional trauma, “It’s Dark and Hell is Hot” made DMX commercial hip-hop’s unlikely successor to Tupac.

On X’s classic debut album, he opens up about a troubled childhood filled with hospital visits, jail stints, unrelenting abuse from his mother and the impacts of poverty on his deteriorating mental state. During a time when most rappers maintained a traditional machismo image, DMX evaluated the human condition while incorporating concepts discussed in college psychology courses.

Everything in DMX’s world was dark, and “It’s Dark and Hell is Hot” detailed the gritty struggle of a man surrounded by inner demons and concrete in Yonkers, NY.

As a kid, X was kicked out of school multiple times for stabbing classmates in the face with pencils, throwing chairs at teachers and planning to burn down his school building; Simmons’ rage lay in other people’s constant attempts to control him.

The video for the lead single “Get at Me Dog” went against everything in mainstream hip-hop at the time. While Puff Daddy and Bad Boy Records created the “shiny suit era” with extravagant parties and silk designer suits, DMX was performing in grimey underground hip-hop clubs, where he would ask over-packed rabid crowds to bark like dogs.

“Ruff Ryders Anthem” was the spark that provided the DMX revolution with a song every rebel could get behind. Despite the track’s gritty sound and X’s aggressive delivery, the rapper still admitted how trauma and pain impacted him. On the album’s most well-known track, X professed his fatigue with fighting authority, acknowledging that he felt like a dog in a cage that wouldn’t be at peace until it was put down.

“Give a dog a bone, leave a dog alone / Let a dog roam and he’ll find his way home / Home of the brave, my home is a cage / And, yo, I’m a slave ‘til my home is the grave / I’ma pull capers, it’s all about the papers / B---hes caught the vapors and now they wanna rape us.”

X spat similar lyrics on “Let Me Fly,” where he explained the environment he was born into was a “curse” he couldn’t escape. He believed he was living in hell on earth: “But you can’t blame me for not wantin’ to be held / Locked down in a cell where the soul can’t dwell / This is hell, come meet the Devil and give me the key / But it can’t be worse than the curse that was given to me.”

One of the most significant themes on “It’s Dark and Hell is Hot” is religion, specifically comparing X’s relationship to the devil with his relationship to God. Constantly in a tug-of-war between good and evil, X’s environment continuously seemed to get the best of him. Infamously turning to robbery as an escape from poverty while in school, he constantly attempted to connect with God, even when he felt a strong pull from the devil.

No track captures that eternal struggle better than “Damien,” which is about DMX’s alter ego attempting to seduce him into hedonistic behavior. DMX is desperate, so Damien’s demands seem like the only choice, but once the evil voice requests X to kill a close childhood friend, it’s a clear omen for X that Damien is nothing but trouble.

The influence of “Damien” runs deep in hip-hop, as modern-day superstars like Kendrick Lamar have worn DMX’s influence on their sleeves. On his critically-acclaimed 2015 album “To Pimp a Butterfly,” Lamar has a conversation with the devil similar to X’s, except Lamar’s seducer is named “Lucy.”

Eminem’s “Slim Shady” character has a similar conversation with Dr. Dre on the pair’s 1999 hit single “Guilty Conscience,” while Tyler, the Creator names the voice in his head “Wolf Haley,” who makes numerous appearances on Tyler’s first three albums.

Even incorporating a prayer skit in the album (and every album that followed), DMX made his trials and tribulations with God well-documented.

X’s attempt to reconnect with God on “The Convo” plays like a back-and-forth conversation, just like his interaction with Damien. Once he initiates the “conversation,” he explains that he robs people out of necessity, not desire. He questions why God would place him in the worst position possible — a poverty-stricken single-parent home with an abusive mother and temptations surrounding him at every street corner — if he wanted him to succeed.

“That with all the blood here, I’m dealin’ with Satan / Plus with all the hatin’, it’s hard to keep peace / Thou shall not steal, but I will to eat / I tried doin’ good, but good’s not too good for me / Misunderstood, why you chose the hood for me?”

While X often turned to God to rescue him from his seemingly eternal darkness, he succumbed to the devil many times. With rampant homophobia and threats of child rape, DMX was by no means a perfect man.

“X-Is Coming” features DMX possessed by the devil while he sings a Freddie Krueger nursery rhyme and details the actions he’ll take against his enemies. He was infatuated with the darkness because anything could happen there, and despite attempting to be a devout Christian, he couldn’t get over the adrenaline rush of fighting authority and embracing his evil temptations.

DMX’s constant struggle with religion and his complicated relationship with God is a direct result of his childhood trauma. As a child, Simmons was beaten so severely by his mother and her various boyfriends that he lost multiple teeth. He slept on cold floors and was greeted by mice and roaches throughout the night. An aunt even got him drunk on vodka when he was seven.

When Simmons was 14, he ran away from home and began living on street corners to escape the cycle of abuse and poverty that befell his family. He befriended stray dogs and began to trust them more than people. He would sleep outside, trusting the dogs to protect him from the dangers of the streets.

Thus explaining his infatuation with dogs and the darkness, Simmons’ identification with canines became a personality trait of DMX.

“Look Thru My Eyes” opens with the audio of a whimpering dog before X expresses his paranoia based on his life’s previous trauma: “Burnin’ in hell, but don’t deserve to be / Got n---as I don’t even know that wanna murder me / Just because they’ve heard of me, and they know that the Dark is for real / The bark is for real, when you see that spark it’ll kill.”

While DMX is in a vulnerable emotional state for the entirety of the album, his relationship with dogs gives him a sense of confidence he would have never had otherwise. As a young kid roaming the streets, X was comforted by canines, who offered him a loyal partner in a world seemingly devoid of loyal partners.

“You think a lot of ‘em’s tough? That’s just a front / When I hit them n---as like, ‘What you want?’ The battle turns into a hunt / With the dog right behind n---as chasing ‘em down / We all knew that you was p--sy, but I’m tasting it now / And never give a dog blood, ‘cause raw blood will have a dog like what? / Biting whatever, all up in your gut,” he rapped on “Intro” — a track so menacing Mike Tyson used it as his walkout song for his return to boxing against Francois Botha in 1999.

“It’s Dark and Hell is Hot” is one of the most unique stories in hip-hop history. Childhood trauma and poverty forced Simmons to live a life he never wanted to live, but through an infatuation with dogs and the darkness, Simmons found a new identity: DMX. Battling through the constant struggle of good versus evil and a need to belong, DMX tells one of the most compelling stories in hip-hop history.

Unfortunately, the story of the album was so authentic it followed DMX throughout his life.

Simmons was arrested 30 times, had 15 children with nine different women and was accused of missing multiple child support payments throughout his lifetime.

He also developed a serious addiction to crack cocaine at a young age. He claimed that when he was 14, DJ and mentor Ready Ron laced a blunt with crack without his knowledge, spurring what would become a lifelong addiction. X also claimed that he was diagnosed as bipolar as a result of his childhood trauma.

X entered rehab multiple times and had to cancel concerts in 2002, 2017 and 2019 to seek help.

When asked if he has a drug problem in a 2013 interview with the Oprah Winfrey Network, DMX told Iyanla Vanzant, “I will always have a drug problem… Just because you stop getting high doesn’t mean you don’t have the problem because it’s a constant fight every day. Every trigger that was a trigger back then is still a trigger, whether you act on it or not is something different. But I will always, until I die, I will always have a drug problem.”

Vanzant then asked X if he wanted to live a clean life, to which Simmons replied, “Why? Why would I?”

Despite his serious addiction, Simmons always claimed to have a great relationship with God.

“That’s why God gives me the blessings that he’s giving me,” DMX said during the interview. “Everybody’s time is running out… if I drop dead right now, I will have fulfilled the purpose that God had me to do.”

On April 2, Simmons was rushed to White Plains Hospital after suffering a heart attack as a result of a drug overdose. On April 9, he was pronounced dead at 50.

One of the most influential artists ever, DMX died holding some of the greatest accomplishments in hip-hop history.

After the release of “It’s Dark and Hell is Hot,” DMX released his sophomore album “Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood” seven months later, in December 1998. It sold over 670,000 units in its first week, making DMX the first living hip-hop artist to have two albums released in the same year debut at No. 1 on the U.S. Billboard 200 (Tupac accomplished the same, but he did so posthumously, in 1996).

In fact, his first five albums each debuted at No. 1 on the U.S. Billboard 200.

He’s the only rapper to ever achieve such a feat.

The impact of DMX and his Ruff Ryders crew — which originally consisted of himself, Swizz Beatz, and The Lox (Jadakiss, Styles P and Sheek Louch) — could be heard worldwide, and provided a gruff alternative to commercial hip-hop’s “shiny suit era.”

DMX became one of hip-hop’s most successful stars by remaining authentic to himself and telling his story, including the good, the bad and the ugly.

To fully understand the DMX’s impact, it seems one just had to be there.

An iconic clip of what appears to be the entire world watching X perform at Woodstock 1999 encapsulates the power of the DMX movement, as an estimated crowd of 400,000 goes absolutely berserk for anything X does.

In hindsight, the most important lyrics on “It’s Dark and Hell is Hot” come from “I Can Feel It,” a track that samples Phill Collins’ “In The Air Tonight.”

Nobody understood DMX, and it seems that even when he called upon God to help him, he was always searching for answers.

“When I make that you fake cats have violent dreams / It takes another dog to be able to hear my silent screams / The Devil got a hold on me, and he won’t let go / I can feel the Lord pullin’, but he movin’ dead slow / Let ‘em know that amidst all this confusion / Some of us may do the winnin’, but we all do the losin.’”

Through severe levels of emotional depth and a captivating origin story, DMX was the closest entity hip-hop ever had to another Tupac.

X’s troubled childhood created a monster nobody could contain. Despite his unmatched energy and lyrical talent on the microphone, Simmons could never escape his inner demons.

“It’s Dark and Hell is Hot” is DMX’s essential album, and in hindsight, it plays like an extended obituary.

In his quest for salvation, the unforgiving concrete of the streets constantly pulled Simmons back to his agonizing beginning.

After battling through the ups and downs of No. 1 albums, childhood trauma, drug abuse and a never-ending search for love, the dog can finally rest.

If you or someone you know has an addiction or mental health problem, you can reach the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357.

Anthony DeCicco is the Senior Sports Editor and can be reached at anthony.decicco@ubspectrum.com and @DeCicco42 on Twitter

Anthony DeCicco is the Editor-in-Chief of The Spectrum. His words have appeared in outlets such as SLAM Magazine andSyracuse.com. In 2020, he was awarded First Prize for Sports Column Writing at the Society of Professional Journalists' Region 1 Mark of Excellence Awards. In his free time, he can be found watching ‘90s Knicks games and reading NFL Mock Drafts at 3 a.m.