In 1993, UB hosted the second-largest sporting event in the world.

That year, more than 7,000 athletes from 137 countries descended on UB for the World University Games, a multi-sport competition organized by the International University Sports Federation. For a few fleeting moments, the City of Buffalo was at the center of the collegiate sporting universe.

But 27 years later, few students have heard of these games. Even fewer know that Buffalo was the first and only American city to host the summer event — that is, until they are held in Lake Placid in 2023. There is just one known marker of the games on campus — a plaque outside of UB Stadium commemorating them.

Other than that, the event doesn’t show up anywhere.

Except, of course, in the numerous areas that it does.

It is difficult to overstate the impact the games have had on UB Athletics: without them, UB likely would not have made the leap to Division-1A or been ranked in the top-15 in men’s basketball or had a 30,000-seat football stadium on campus.

“I don’t think you can argue that,” said Pete Bothner, Nazareth College athletic director and former assistant athletic director for facilities and event operations at UB. “It gave them a facility that allowed you to say we’re going to move and be a legitimate Division I competitor.”

The story of the 1993 Summer Universiade is one of ambitious promises and tempered results; of international competition and local derision; of what happens when a city tries to rehabilitate its image but ends up complicating it.

Origins

On May 2, 1989, Sens. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) and Alfonse D’Amato (R-NY) submitted a resolution to the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation in favor of the World University Games being hosted in the U.S.

Resolution 31 argued that the World University Games “have a long and demonstrated record as a premier international amateur sports event;” “exemplify the heritage of peace and goodwill associated with amateur sports competition;” and present an “exceptional opportunity for the athletes from the different nations of the world to share their cultures with each other and the citizens of the United States and New York.”

Led by Burt P. Flickinger, a respected businessman and philanthropist, local leaders aggressively pursued a bid to host the games. The Greater Buffalo Athletic Corp. competed with the cities of Shanghai and Fukuoto, Japan to bring the summer event to the U.S.

Former Erie County Executive Dennis Gorski speaks at the World University Games '93.

On June 16, 1989, with support from prominent leaders like President George H.W. Bush, Gov. Mario M. Cuomo and Erie County Executive Dennis T. Gorski, the City of Buffalo was chosen to host the 1993 games.

Politicians cited massive anticipated crowds — approximately 120,000 spectators, including more than 50,000 from outside the U.S. — and global coverage — an estimated 2,000 media members would be in attendance — in the run-up to the event.

Speaking in 1989, former UB President Steven B. Sample said that the ‘93 games “will provide an excellent opportunity for tens of millions of people around the globe to see our city and our university in the best possible light.”

He noted the last time the City of Buffalo hosted a world-class event, the 1901 Pan American Exposition, President William McKinley was assassinated. The 1993 games are “our best opportunity in a century to showcase Buffalo and Western New York for the rest of the world,” he said.

Hiccups

Vicki Mitchell, the director and head coach of UB’s track and field and cross country teams, was a college student at North Carolina-Greensboro when the local Buffalo newspapers began reporting on the ‘93 games.

“Up to that point, I hadn’t heard what this competition was,” Mitchell said, “but I thought, ‘Wow, that sounds pretty cool.’ Pretty soon, I started to grasp the enormity of the games. I have a ton of pride in the City of Buffalo. What can be more incredible than watching a bunch of the [best] athletes in the world competing?”

Looking through old newspaper clippings from the early 1990s, it isn’t difficult to see why Mitchell would be excited. Not only was the City of Buffalo expected to bring in thousands of top athletes and spectators, but there was the promise of a profound economic impact on Western New York.

Edmonton-based Nichols Applied Management estimated that the Buffalo area could gain as much as $150 million in economic benefits and more than 2,400 jobs. The firm also calculated that state and local governments would receive $9.3 million in added tax revenues.

But before Buffalo could reap the economic rewards of the games, it had to figure out how to break even on a $32 million budget, which meant securing sponsorship deals and selling out 65,000-seat Rich Stadium, the former home of the Bills and the site of the game’s opening ceremonies.

Local leaders struggled to build public support for the games. Politicians flip-flopped on supporting them. Vendors were hesitant to lend their money. Some residents were thrilled to be a part of something so global; others weren’t quite as convinced.

In the end, the games’ detractors proved correct: the Greater Buffalo Athletic Corp. ran up a $2.9 million deficit. It took more than a year for hundreds of area vendors to receive even half the money they were owed. Some cities that have hosted international sporting events, like the Olympics, learned the hard way that these games are costly and in many cases, hardly profitable.

Buffalo learned the same lesson.

Facilities

“We were trying to build a football program,” Bothner said.

Since 1977, the Bulls had been playing football at the NCAA Division III level.

But under the leadership of Sample, UB began the difficult ascent to Division I. It was tough to build momentum in the community: there were other things to worry about, and besides, hosting a D1 football team — a good one, at least — requires a premier facility.

UB had the 4,000-seat Walter Kunz Stadium, which had previously hosted football, track, soccer and field hockey. But that was it. Making the move to Division I — and especially to the top-level, FBS — would require a stadium that could hold significantly more people.

Enter UB Stadium.

In the lead-up to the games, the state announced it would shell out $22 million for a new stadium on UB’s North Campus. The stadium would consist of a field surrounded by an eight-lane track, which would be used to host the track-and-field events, and later, the university’s football team.

Victor E. Bull and True Blue cheer in the student section at UB Stadium.

“It’s a true facility of the ‘90s,” UB Assistant Athletic Director Bill Breene told the UB Reporter in 1993. “It has everything you would ever need to run a first-class operation. It’s important for us to showcase this facility, not only for our university, but for all of Western New York. We hope that the Stadium will give WNY some bragging rights around the nation.”

Breene hoped that one day, UB Stadium would help the Bulls compete with the Penn State’s and Syracuse University’s of the world. It did.

“From a recruiting and interest standpoint, the new stadium gave the football program and the overall department a boost,” Bothner said. “It gave it a recruiting boost. It told kids we were taking things seriously. We were going to be a solid program. I just don’t think you could have done that on the old turf field they had. It gave the football program the boost it needed to recruit athletes.”

Football wasn’t the only sport to reap the rewards of the new stadium. The track-and-field and cross country teams have also been aided by the structure, according to Mitchell.

“When I’m recruiting, I use that track-and-field stadium as a tool for us, because that truly is a track-and-field stadium,” Mitchell said. “Yes, it also hosts football and soccer and other events. But when you look at the originality of the stadium, you know it was built for track-and-field.”

Now, the track-and-field and cross country teams have two stadiums to train in: UB Stadium and Kunz Stadium. “What other university has that option?” Mitchell asked. “It’s pretty incredible.”

But more than its effect on any single sports team, the facility has had a sizable impact on the entire department. In collegiate athletics, football usually has a trickle-down effect on other sports: If the football team is successful, so too are the other programs.

“I think that once you got that stadium, it allowed the football program to build the momentum to bring in those kids who can make you a perennial winning team,” Bothner said, referencing UB greats like Khalil Mack and James Starks. “I think without football having success, it’s just that much more difficult to be successful in other sports.”

In recent years, the Bulls have enjoyed success across sports: the men’s basketball team has made multiple tournament runs, and was ranked as high as No. 14 nationally; the women’s basketball team has advanced as far as the Sweet Sixteen; the men’s and women’s tennis teams have both won MAC titles; and Jonathan Jones won the shot put title at the NCAA Championships.

Game day

The games kicked off on July 8, 1993, with the opening ceremonies at Rich Stadium.

Bill Clinton officially opened the event. Country music star Kenny Rogers — at a hefty price tag of $150,000 — and Grammy Award-winning pop star Natalie Cole performed. Speaker of the House Tom Foley lit the torch. Parachutists landed to a thunderous applause.

Mitchell, who had qualified to represent the U.S. in the 10,000-meter run, was selected as a flag bearer. She remembers feeling deluged with well-wishers.

“As the athletes marched in, it was like the Olympic games, where they brought in each team, country-by-country,” she said. “I just remember holding the flag and feeling overwhelmed by being in front of thousands and thousands of people.”

At the end of the two-hour opening ceremonies, there was a massive fireworks display that continues to resonate with everyone involved.

“It was an unbelievable fireworks display,” Mitchell said.

“The fireworks display was just second-to-none,” Bothner said.

The more than 4,000 athletes stayed at the Ellicott Complex, which was styled after the Olympic Village. According to the UB Reporter, the university erected a phone bank, a post office, a portable stage, a seating area for meals, a full-fledged bank and the Village Mayor’s Office.

Meals were provided by Service America, which had experience catering large-scale events.

With athletes from over a hundred countries — including some that had hostile relations with the U.S. — security for the event was intense. The school placed 36 surveillance cameras atop buildings and installed three miles of security fencing around the village.

For the next nine days, athletes competed at UB Stadium; the Ellicott Complex Tennis Center; a 50-meter pool at Erie Community College; the Town of Tonawanda Aquatic and Fitness Center; and other venues across the border, in Canada.

“It was awesome,” Bothner said. “We had volleyball and diving in Alumni Arena. We had tennis going on by the Ellicott Complex. We had track in the stadium. It was just a great environment. I don’t think the crowds were overwhelming, but we had a lot of people getting exposed to UB for the first time and I think it helped put us on the map. The weather was fabulous. It was just an exceptional event.”

Legacy

More than 18,000 people volunteered at the games.

The U.S. breezed to a first-place finish, winning 73 medals, including 31 gold medals.

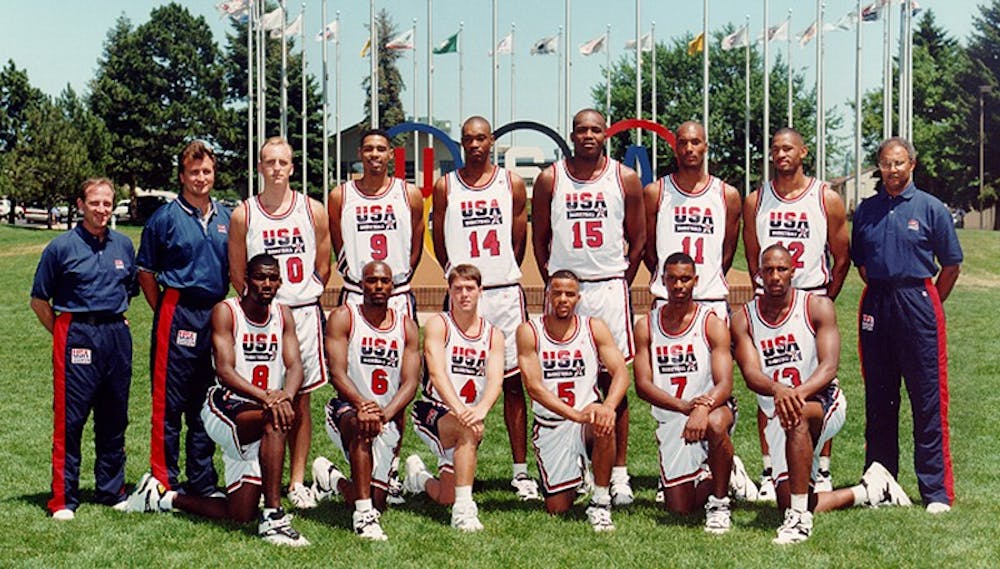

Celebrated athletes, including women’s soccer legend Mia Hamm, men’s basketball star Damon Stoudamire and former Marathon record holder Khalid Khannouchi, competed in front of the Buffalo faithful.

More than 18,000 people volunteered at the 1993 World University Games in Buffalo.

The games went off relatively smoothly; while the financials continued to plague organizers for years after the event, the competitions themselves were largely scandal-free, with two notable exceptions: the 79 student-athletes from the Libyan team were denied entry to the U.S. because of their country’s link to terrorism, and the Cuban baseball star Edilberto Oropesa defected from the national team.

And yet, few people under the age of 30 have heard of the event. Stranger yet, the university has done little to market these games to the younger generation.

“I think part of it is, the people who were associated with putting on that event in the City of Buffalo are now retired, especially the ones that were at the university,” Mitchell said. “I’m probably one of the very few who was involved. The World University Games in general is not a very-well known event. I had never heard of them beforehand.”

Either way, the games have had a long-lasting impact on the university.

“It was an exciting time,” Bothner said. “It was a time we were getting enhanced facilities because this pseudo-Olympics games event was coming on board. I was really excited personally because why wouldn’t I want to be around something like that? It was a really fun time to be around Buffalo.”

Justin Weiss is the senior features editor and can be reached at justin.weiss@ubspectrum.com

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article stated Daniel Patrick Moynihan was a Republican. The story has been changed to reflect that he was a Democrat.

Justin Weiss is The Spectrum's managing editor. In his free time, he can be found hiking, playing baseball or throwing things at his TV when his sports teams aren't winning. His words have appeared in Elite Sports New York and the Long Island Herald. He can be found on Twitter @Jwmlb1.