Film: The Family

Release Date: Sept. 13

Studio: EuropaCorp

Grade: D

Luc Besson's The Family is an extravagant jest about a family of four who relocates to Normandy, France, while hiding in the Witness Protection Program.

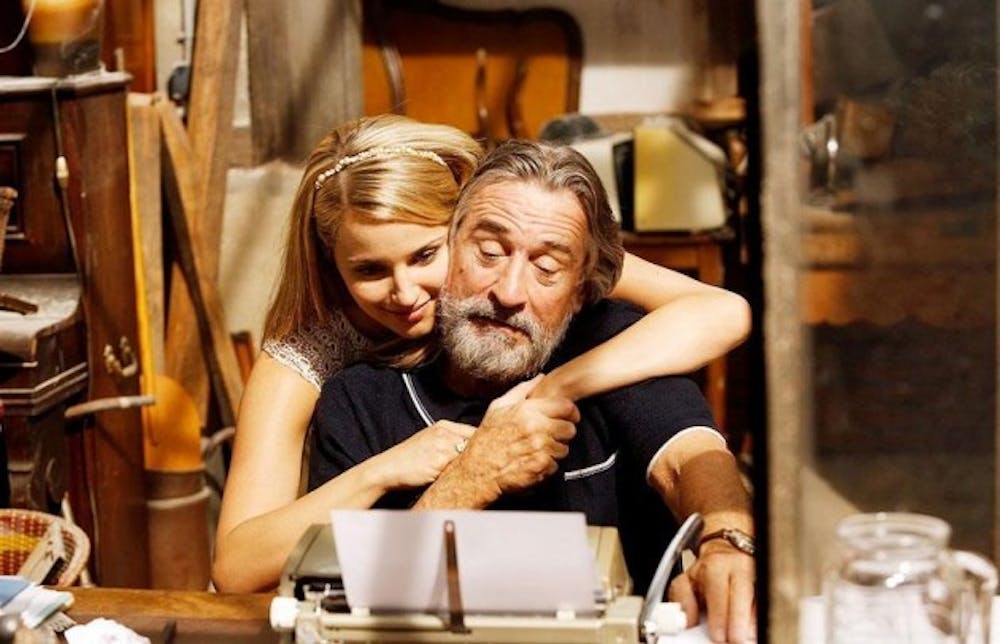

In the first scene, we get an image of a seemingly normal family vacation - a father, a mother, a daughter and son, and their German shepherd - travelling in an SUV at the end of a long road trip. They arrive at the house they are planning to stay at, and once the family vacates the car and everyone begins to settle into their new quarters, Giovanni Maznoni (Robert De Niro, Silver Linings Playbook) dumps a dead body out of the trunk.

It quickly becomes evident that this is no vacation; this is a cyclical routine they go through every few months or so. They are a mafia family and are constantly on the move. This is life as usual for the Maznoni's.

Besson (The Lady), who made his way with Leon: The Professional, seems misplaced in a decadent work of farce. Often criticized for being the most Hollywood-ized of modern French directors, he has now descended too far into an inherent state of unreality.

The screenplay is written by Besson and Michael Caleo (Ironside), and is based on the novel Malavita (Badfellas in English) by Tonino Benacquista. Besson makes it an opportunity to play with the conventions of American gangster films. It is fast paced and modernized, accompanied by a nostalgic score that evokes its past influences - think of what it might look like to merge the styles of Sergio Leone and Martin Scorsese with the vacuous sensibility of Guy Ritchie.

Watching this film unfold is what comes when talent works without direction; the disappointment comes from the sense of movement without purpose. The film is overcharged without any payoffs - it's an empty ride. Besson's joke of exaggeration becomes both homage and parody, and it feels more gimmicky than anything else.

For 112 minutes, insensible violence engulfs the viewer. Giovanni uses a baseball bat and sledgehammer on a plumber who tries to rip him off; his wife, Maggie (Michelle Pfeiffer, People Like Us), blows up a grocery store that doesn't have peanut butter; his daughter, Belle (Dianna Agron, Glee), pummels a creep with a tennis racket; and his son, Warren (John D'Leo, Wanderlust), is something of criminal-in-training at his new school, and on several occasions is overtaken by bursts of bone-crushing brutality.

It is a work of exploitation, a celebration of sadism, a movie of gratuitous bloodshed.

The blonde presence of Pfeiffer alongside an inscrutable male criminal cannot help but prompt consideration of Bonnie and Clyde - a film that paved the way for movies like The Godfather and Mean Streets. Arthur Penn's 1967 film introduced a new level of violence to the American cinema and changed its trajectory - protagonists could now be loveable bad guys. But there was something else central to its importance.

The filmmakers chose to make Clyde impotent. After he and Bonnie meet, they attempt to have sex. When he's unable to and abruptly tells her, "I ain't much of a lover boy," a transition ensues. In the very next scene, he teaches her how to use a gun. They then embark on their notoriously vicious expedition.

Bonnie and Clyde became violent because they needed a replacement for the sexual release.

Besson's film, with all its homage to past works of violent indifference, fails to grasp a central irony. The Family is meant to be a comedy with all its brutal playfulness, but it fails to marshal any type of vital response. The violence is so widespread - so indiscriminately delivered and repetitive - that it empties itself of meaning.

It makes you realize that this is the problem with much of today's commercial cinema: action with no impact.

One thing to notice is the misuse of De Niro's presence. Giovanni is a Mafioso-turned-informant, a rat, with suppressed rage. He's inarticulate yet aspiring to be a writer. But Besson makes him not suppressed enough. Scorsese knew the power of De Niro was the way he could embody that sense of having a force deep inside him that could explode any minute. It was the threat, the possibility of explosion that he could carry for an entire film. And when he did finally burst, we felt a visceral, gut reaction.

Pfeiffer plays a ditsy Brooklyn housewife, sloppy and without scruples. She casually admits to having lost her virginity in a cathedral, and her confession to one of the French priests manages to get her ostracized from the local church - she's beyond absolution. Though she's thoughtful enough to make a nice home-cooked Italian meal for the FBI agents guarding her family - "roasted peppers with olive oil and a lot of garlic."

Besson makes the daughter the angelic, ethereal figure - the blonde garbed in white. One of the most engaging threads of the whole film is when she presumes herself a tragic victim after she's rejected by the young Frenchman she thought was the light of her life. Her moments of dismay become a satire of the pre-packaged drama that comes out of Hollywood teenybopper movies. She also can go from being an innocent virgin to an American-girl badass. She batters lustful French schoolboys, who take flirtation too far.

Tommy Lee Jones (Lincoln) graces the screen as FBI Agent Stansfield, who oversees the Moznani family's most recent relocation. He provides one of the few enjoyable performances in the film. Vincent Pastore (Once Upon a Time in Brooklyn) is a delight because he reminds us that it wasn't long ago he was in The Sopranos.

At the end of this film, one is likely to feel nothing - no emotional attachment to the characters, no concern over what the film has to say. Despite its seasoned director and impressive cast, its overwhelming inanity defuses any possibility of enjoyment.

One thing Besson and other filmmakers need to get is that the cinema is sensuous in its nature and, since its early days, violent depiction has been a key ingredient as to why it's a source of pleasure for the masses.

But when violence is ubiquitous, it's less significant. If it's everything, then it's nothing. When it becomes fused in our automatic expectations, its usage loses power.

Email: arts@ubspectrum.com