On Friday, April 5, a federal judge ordered the morning-after pill be made available over the counter for girls of all ages - putting an end to age restrictions on the accessibility of emergency contraception.

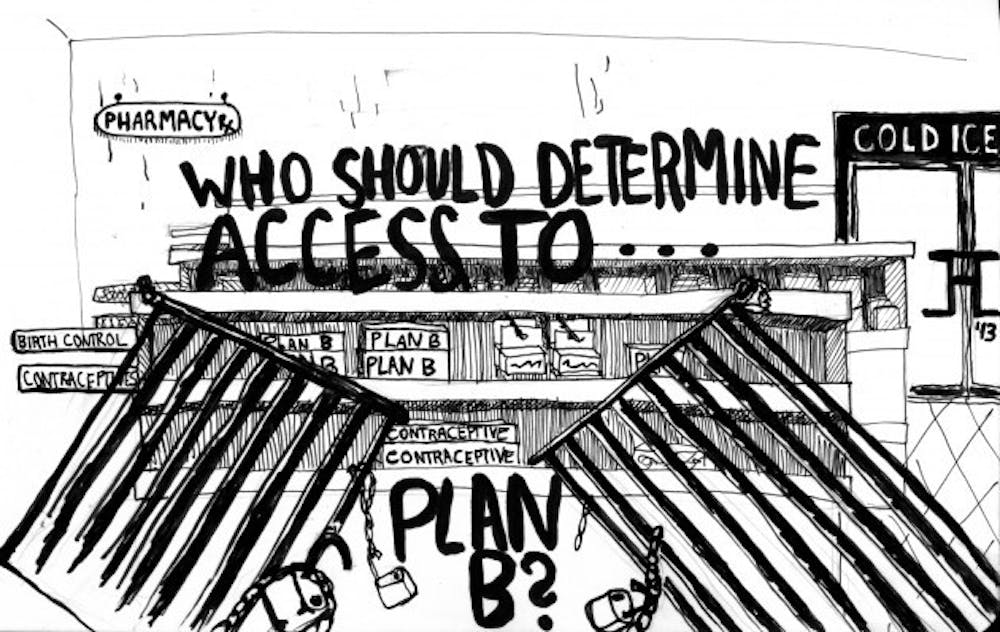

We believe there should not be restricted access to emergency contraception, regardless of any politics. Placing certain requirements that force young girls to go through a process of delay in a predicament that entails immediate action is a matter of safety.

The ruling deals specifically with the most common morning-after pill, Plan B One-Step, making it now available to girls ages 16 and younger without having to get a doctor's prescription to obtain the pill.

Judge Edward R. Korman of the U.S. District Court of the Eastern District of New York provided the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) 30 days to remove any age or sales restrictions on Plan B One-Step and other generic versions of the drug.

The case was brought to the courts by a group of young women, as Kathleen Sebelius, secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, overruled the FDA's original decision to widen the availability of the pill in Dec. 2011.

As Korman sided with the FDA, he criticized the move by Sebelius and the Obama administration as being politically motivated rather than following standard agency procedure, which would have to comprise a challenge dealing with the safety and effectiveness of the drug.

Their rejection of over-the-counter access came during the president's re-election campaign and was, in our eyes, in the interest of not alienating voters through a divisive and polarizing issue.

Now, by federal ruling, the Obama administration's stance on this specific issue, which is the traditionally more conservative one, has been struck down.

The term 'morning-after pill' is a misnomer itself. In order for the pills to have the highest level of possible potency at disrupting ovulation or fertilization to prevent a pregnancy, they need to be taken as soon as possible. For a young girl who is need of the pill, to have to go through the steps of seeing a doctor (which is not always the most speedy process) and to have to get a prescription and not have direct access to the pill promptly, it reduces the safety and efficacy of the drug.

Not all teenagers have access to transportation and they may need their parents' help to even physically get to the doctor's office - and it is not always comfortable for an adolescent to share information regarding his or her sex life with parents. Plus, that is not even considering the possible ideologies and beliefs of each teenager's parents. All kinds of possible factors incur as you consider this issue further, and it is not fair to let individual components impact one's ability to get the medical treatment she needs.

The indirect circumstances the FDA and government facilitate directly affect the way young teenagers interact with this drug.

This is not a new concept, either. For many years, scientists have been recommending unrestricted access, according to The New York Times. Medical researchers from agencies and groups like the American Medical Association, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Pediatrics and even scientists at the FDA have asserted that conditions which limit teenagers from being able to take the drug in the proper timeframe encompass even greater safety risks than the pill itself.

Conservatives who have criticized the judge's ruling have implied that terminating the requirement of having teenage girls visit a doctor prior to obtaining the pill will put them at a greater risk for contracting sexually transmitted diseases that will go undiagnosed and untreated. They have also opined that this governmental policy promotes sexual activity for those who are not developmentally prepared for it.

The latter argument carries some weight, though it is plainly na??ve. In Buffalo, 16 percent of middle school students are having sex, according to the Buffalo Public Schools 2011 Youth Risk Behaviors Survey.

The fact remains teenagers are having sex (and lots of it), and the government should not stand idle and allow restrictions to impede their ability to receive the same contraception that is available to the rest of the general public.

It is important to practice empathy in dealing with these matters when a policy like this will affect the real lives of real people. We have to extend our imaginations beyond the mere textbook cases and consider those whose circumstances are different from and more challenging than others.

The possible consequences of teenage girls not having direct and immediate access to emergency contraception pills are serious, and if we want to help them avoid a more difficult situation, this is a good step.

Email: editorial@ubspectrum.com