Seven hundred ninety-two students have received medical or religious exemptions from UB’s COVID-19 vaccination requirement as of March 21, according to Student Health Services data. Of those students, 769 have a regular presence on campus, while the remaining 23 are taking entirely remote coursework for the spring semester.

Not every exempt student is necessarily completely unvaccinated. Although all exempt students lack a booster shot, some may have received one or two doses before applying for an exemption due to changing medical or religious circumstances, according to SHS director Susan Snyder.

Students cited a wide range of reasons for choosing not to get vaccinated, according to redacted copies of approved COVID-19 vaccine exemption applications obtained by The Spectrum through a Freedom of Information Law request. The 80 applications obtained — totaling six medical exemptions and 74 religious ones — represent every medical and religious exemption approved by SHS between Aug. 31 and Dec. 31, 2021.

At least 38 students, representing just over half of all applicants, cited some sect of Christianity as the reason for the exemption, but students filing under Sihkism, Scientology, Islam, paganism, a traditional African religion, Judaism and the United Congregation of Universal Wisdom were all approved for exemptions.

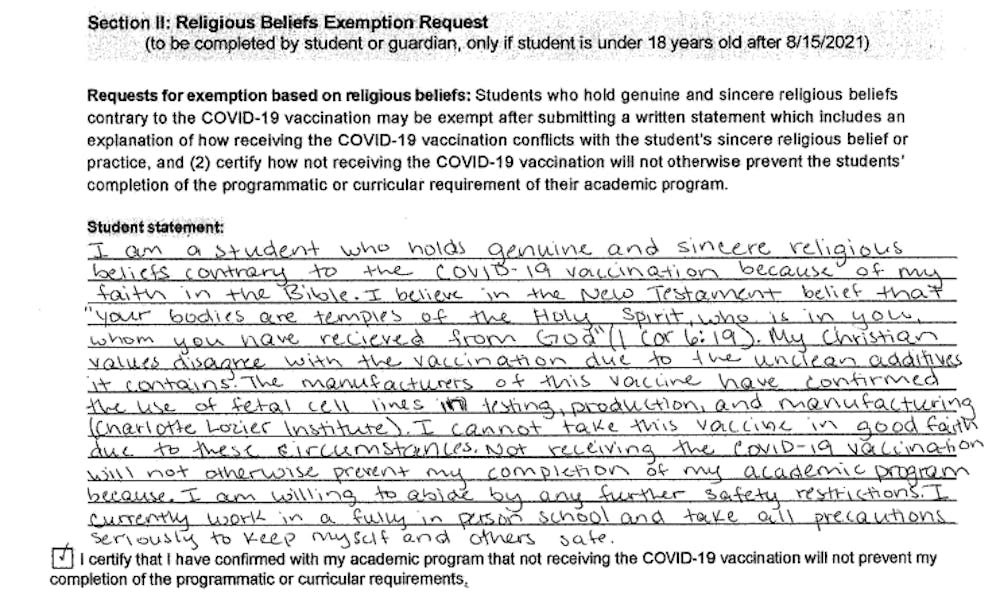

Students most commonly described the “usage of aborted fetal [stem] cells at any stage in the vaccine [development] process [that] violates a pro-life religious stance,” the belief that the vaccine puts “unclean additives” or “impurities into [the] body” and the conviction that “any medical interventions” like vaccines “would be a betrayal of faith and a betrayal of trust in God” as reasons for their objections, to quote students’ statements.

Far fewer (six) students were approved for medical exemptions. Half cited an immediate anaphylaxis and allergic reaction to the COVID-19 vaccine, with the rest citing myocarditis or MIS-A (Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults).

The list of exemption-worthy criteria was based on CDC guidance, Snyder said.

To apply for a religious exemption, students had to properly complete UB’s exemption request form, promise to follow COVID-19 guidelines, affirm that a lack of vaccination would not impede their academic progress and provide a personal statement attesting to a specific religious belief that morally prevented them from getting vaccinated.

Students weren’t required to disclose their formal religious affiliation — or even to have one — but applications containing political, philosophical or personal beliefs were denied, Snyder said. Students who requested exemptions after receiving at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine had to explain what changed their beliefs or circumstances.

Most students’ religious exemptions were accepted on the first submission, Snyder said. But in the event that a student’s request was denied, SHS allowed them to submit as many follow-up request forms as they wanted, as long as each new form contained new information.

“The student really has the right to try to articulate their religious beliefs, and we can’t really cut them off from that ability to resubmit,” Snyder said.

After the mandate went into effect, SHS began educating students who cited misinformation as the basis for their exemption request. For example, Snyder says if a student objected to taking a vaccine containing fetal stem cells, SHS would point out that fetal stem cells were only used in research and development, although Snyder said that fact checking “generally did not” change students’ choices.

SHS says it did not attempt to verify religious beliefs beyond what students stated in their applications.

“If they were able to articulate their religious belief and tie it to the COVID-19 vaccine, then it wasn’t really for us to judge their religious belief,” Snyder said. “There was no check. We didn’t go to any external source, …partially because [exemptions] weren’t necessarily based on a formalized religion.”

The line between religious and non-religious reasons to refuse the vaccine can sometimes be blurry. Yasmeena Chambers, a junior psychology major, genuinely felt that her Rastafarian beliefs called on her to use herbal medicine instead of modern medicine, but admitted that her discomfort with taking such a recently developed vaccine was the bigger factor.

“My family does have a lot of health issues, so I felt scared to do it because I wasn’t sure how my body would react,” Chambers said.

Chambers is currently taking a semester off from her studies to work and plans to get vaccinated before returning to campus in the fall.

Students seeking a medical exemption went through a similar application process but were required to provide contact information for their healthcare provider and a valid medical excuse instead of a personal statement. A senior physician at SHS reviewed all medical exemption applications.

But not everyone who thought they needed a medical exemption got one. Andrew Hughes, a junior business major, experienced heart palpitations after receiving both doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, despite having no history of heart problems.

“I got my second vaccine [dose], and that day, it was really f—ing bad,” Hughes said. “I was laying on my floor. I thought I was literally about to die. My heart was racing out of my chest.”

Hughes says his cardiologist at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City thought the cause was most likely myocarditis caused by the vaccine. They helped Hughes apply for an exemption twice. Both requests were denied because Hughes’ doctor couldn’t say with 100% certainty that the COVID-19 vaccine caused the palpitations.

Hughes weighed getting the required booster dose, but decided against it due to the health risks. He switched to an entirely online course load that won’t fulfill any of his major requirements, which will force him to stay at UB an additional semester. He says he misses being able to go to lacrosse practice and meet friends in the library.

“I’ve basically been online for the last two years straight,” Hughes said. “I was stoked to come back… [Now,] I’m sitting at home all day.”

Exempt students with an on-campus presence are required to undergo weekly surveillance testing. Students who miss two weeks of testing in a semester, consecutive or otherwise, generally have 3-5 business days to get tested before being deregistered from their classes for the remainder of the semester. The number of students deregistered for non-compliance this semester has been “pretty low,” Snyder said.

Students are no longer required to wear masks on campus “regardless of vaccination status.”

An additional 391 students received vaccine exemptions because they were completing entirely remote course work, up from 274 during the fall semester. Students with remote exemptions must reapply every semester and agree not to set foot on any SUNY campus. University officials continually verify that remote exemption applicants are only signed up for remote courses, Snyder said.

SHS is continuing to accept exemption requests from students who are new to UB.

Approximately 97.59% of in-person UB students have received a COVID-19 booster shot.

UB has 15 active cases of COVID-19 and a 0.7% positivity-rate based on a 14-day rolling average as of Tuesday, March 29, according to SUNY’s COVID-19 dashboard.

Alex Falter and Kayla Sterner contributed reporting to this story.

Grant Ashley is a senior news/features editor and can be reached at grant.ashley@ubspectrum.com

Grant Ashley is the editor in chief of The Spectrum. He's also reported for NPR, WBFO, WIVB and The Buffalo News. He enjoys taking long bike rides, baking with his parents’ ingredients and recreating Bob Ross paintings in crayon. He can be found on the platform formerly known as Twitter at @Grantrashley.