Sharon Nolan-Weiss believes Betsy DeVos’ decision to rescind guidance letters for students with disabilities is sending a message that the Department of Education is pulling back on its commitment to civil rights.

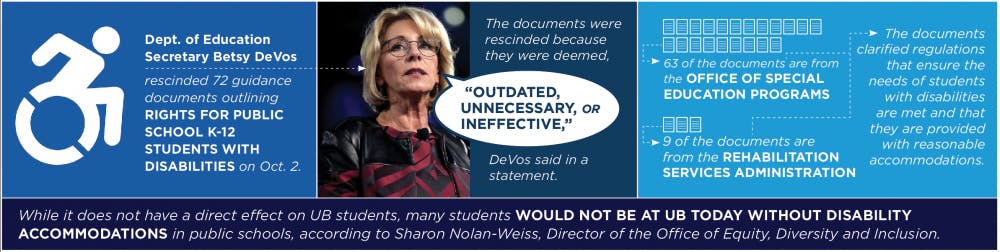

On Oct. 21, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced that the Department of Education had rescinded 72 policy documents for disabled students as of Oct. 2.The documents were rescinded because the Department of Education felt they were “outdated, unnecessary or ineffective.”

Many of the documents outlined how the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act works. Several documents were replaced with more updated guidance letters. For example, the Department said it rescinded a 2006 document that explained the rights of students with disabilities in private schools because the document had been updated in 2011. The department also cut a 2012 letter, which outlines the rights of preschoolers with disabilities that was updated in 2016.

One document that does not have a replacement is a guidance letter that makes it clear how schools can spend federal money set aside for special education. Another document entitled “Questions and Answers on Serving Children with Disabilities Placed by Their Parents at Private Schools,” which translated legal jargon into plain English to help parents understand their childrens’ rights and advocate on their behalf, does not have a replacement either.

“If you’re a parent and you want to know ‘what are my rights for my child,’ those guidance documents were really helpful because they are kind of a plain language way of understanding what the school district is supposed to be doing,” Nolan-Weiss, UB’s Director of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion said. “So I think that’s where some of the major concern has been.”

Hannah Mechanic, a junior health and human services major, expressed similar concerns.

“When it comes to middle school and elementary school students, it’s the responsibility of parents and teachers to be advocates for these students because they simply can’t be advocates for themselves in most scenarios,” Mechanic said. “This entire situation infuriates me because without those guidelines many of the people who would be advocates for students wouldn't know how.”

Nolan-Weiss is concerned that parents of students with disabilities at the K-12 level will be hesitant to advocate for their child’s rights—especially considering the plain language documents that described their rights and resources have been rescinded.

“It creates a question of ‘if I go forward with a complaint, is the federal government going to be interested in upholding my rights?’” Nolan-Weiss said. “But I do know based on things I hear, especially parents of students with disabilities, they are very alarmed that the Department of Education rescinded these without, from what I understand, a whole lot of notice that they were going to do that.”

She feels the Trump administration has a pattern of withdrawing guidance documents; first for transgender students in February of 2017 and more recently, the rescinded Title IX guidance letters.

“So they’ve created this impression that the Department of Education is pulling back on its commitment to civil rights,” Nolan-Weiss said. “[The Trump Administration] will tell you that’s not the case, but I think that is the impression people are getting.”

Justine Grundy, a student teacher and education major at Buffalo State, believes the decision to rescind the guidance letters is “a total rollback” of the progress that had been made to meet the educational needs of students with disabilities.

“People need to care about the rights of students with disabilities,” she said. “It’s unfair to treat them as though they don’t matter as much. I have worked with students who could give so much more, but they are asked less because they have a disability.”

Nolan-Weiss believes disability laws in the U.S. have been “so effective,” and one of the biggest “success stories” for K-12 students with disabilities.

“We have students here at UB who wouldn’t have had a shot if they didn’t have an appropriate public education at the K-12 level for somebody who may have a learning disability and need accommodations in some other way,” Nolan-Weiss said. “They have an effective program that will help them succeed…[and] be able to get in [to college.]”

While DeVos’ move to phase out guidance letters for students with disabilities will not affect UB students with disabilities, Nolan-Weiss emphasized the resources available for UB students with disabilities.

UB has a reasonable accommodation policy, as a way of implementing laws and rules that require the university to provide reasonable accommodations for employees, according to Nolan-Weiss. Students have the right to academic adjustment—the term for “reasonable accommodation” at the postsecondary level.

Any student who requires an academic adjustment or auxiliary aid can go to the Accessibility Resources Office, according to Nolan-Weiss.

“That office does a really good job in terms of accessing what a student needs to succeed and interfacing with the professor as well,” Nolan-Weiss said. “If there’s an issue with an accommodation or an academic adjustment or a disagreement about whether it should be provided, then that would come to my office and we would look at that under the discrimination and harassment policy, because ultimately, denying a needed accommodation or academic adjustment can be a form of discrimination.”

Maddy Fowler is a news editor and can be reached at maddy.fowler@ubspectrum.com