Mustafa Al-Adhami drove to the Canada-U.S. border at 2 a.m. Saturday.

He couldn’t sleep. No one at the customs office had answered his calls, he couldn’t bring himself to read any more news, but he had to know what would happen when he reached that border.

Would he be allowed into the country he called home?

Al-Adhami, a senior chemical engineering major, came to the U.S. in 2012 as a refugee.

The officers asked Al-Adhami to step out of his car and follow them for a “random interrogation.”

Six hours later, he was released. The officers asked about his Iraqi heritage, fingerprinted him twice, took two sets of headshots, went through his phone, his car and the rest of his belongings.

Since President Donald Trump issued an executive order banning travel from seven Muslim nations, protests have broken out in airports around the world. Green-card holders who live, teach, work, or attend school in the U.S. have been detained at airports and border crossings.

Many Muslim students did not feel safe sharing their stories and they did not want their photos or names to be used.

Those who did feel safe to speak up want their peers and colleagues to read their stories and understand how many of them feel at this time.

Coming to America

Ahsanul Haque’s father, an immigrant, worked in the U.S. for 17 years before finally traveling home to see his mother.

Haque, a freshman business major, said immigrants from Iran and Iraq today come to the U.S. for the same reason his father did: a better future for him and his family.

“It’s the land of opportunity, right? My dad saw that if he could come here it would help us too, I could get my education,” Haque said. “It’s the opportunities that we get, that’s what our parents love to see – I think all parents want to see their kids be successful. It doesn’t matter what race or religion you are.”

This vision of the U.S. has faded over time, as the excitement wore off and Haque’s family began to adjust to Muslim-American life.

Haque’s cousins, who still live in Bangladesh, still see that vision of the U.S.

“They look up to America, you know that right? They have this mindset, they’re like ‘oh I want to come to America and if you ask them why they say ‘oh the streets are made out of gold.”

When Mahfuj Uddin’s family emigrated to the U.S. from Bangladesh in 2011, they left behind everything: their assets, friendships and sense of purpose. Uddin, junior biomedical sciences major, said the transition was hard, especially on his father.

His father couldn’t walk through the bazaar without stopping to shake someone’s hand or greet someone. When he came to the U.S., he lost that.

“He doesn’t have that feeling anymore, he doesn’t know people, people don’t respect him like that and at his age, 56-years-old. I don’t want to think of myself at that age coming to a new country with a new language, new culture, adjusting to that,” Uddin said.

Uddin’s family sent his father back home regularly in the beginning to help with the depression and loneliness.

Still, Uddin said he considers his family’s sacrifice small compared to the refugees fleeing war-torn countries like Syria or Sudan.

“That’s when I think about the betrayal that I felt immediately after the executive order, because people come here with the dream and the hope that we’re welcoming them and accepting them because they’re going through so much,” Uddin said. “…So once you see things like that you’re like did I actually make the right decision?”

Perception of Islam

Albert Mashkulli, a sophomore mathematics and political science major, is from Albania, a Muslim-majority country near Greece. Mashkulli said people only hear what the media tells them about Islam.

“There’s about 1.7 billion Muslims in the world; if we’re all extremists or terrorists then the whole world would be destroyed,” Mashkulli said. “The root word for Islam is ‘salam,’ which means peace in Arabic and if that can’t explain what the religion is actually about, then I don’t know.”

Haque said Islam, like all religions, is about peace and ISIS doesn’t represent Muslims anymore than the KKK represents Christians.

Rezwan Karim, a junior electrical engineering major, said it is too late to rely on protests; he believes change needs to start with Trump.

“Trump is trying to stop terrorism by stopping immigrants butwhat he doesn’t see is that America is a nation of immigrants from the beginning.”

Islamophobia, or a dislike or prejudice against Muslims or those who practice Islam has been on the rise since the attacks on 9/11. Terrorist groups like ISIS, who mercilessly kill hundreds of innocent people, exasperate these fears.

Although ISIS has statistically killed more Muslims than non-Muslims, many people remain ignorant of these facts, according to Karim.

“Terrorism isn’t Islam, it’s extremism and that can come from any religion, any nation,” Karim said.

After the ban

Uddin said even though his country wasn’t banned, he wouldn’t feel comfortable traveling outside of the country. He said there is a growing fear that Trump’s policies will expand to include more Muslim-majority nations.

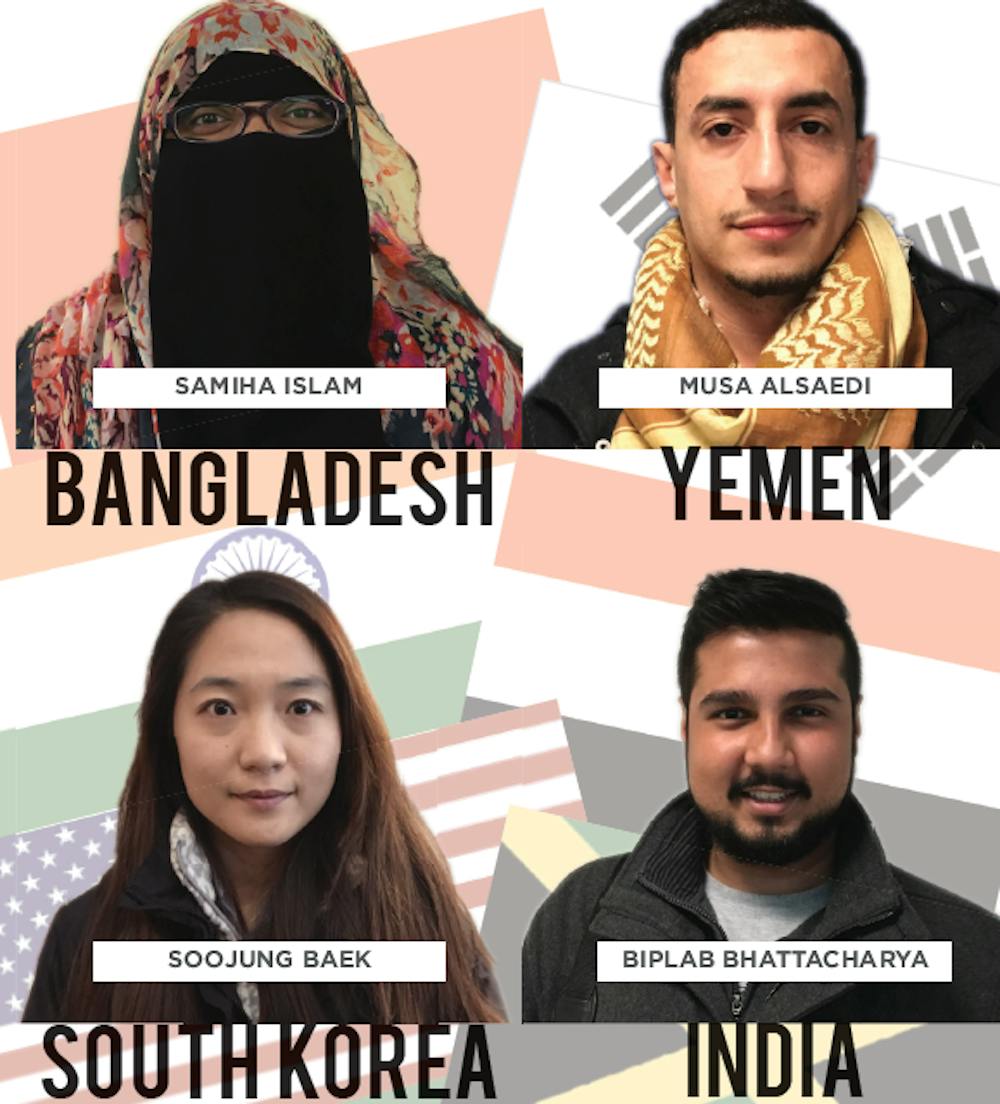

Musa Alsaedi, a senior civil engineering major, was born in Yemen, one of the nations banned. His family has lived in the U.S. for four generations now.

Alsaedi’s uncle owns businesses and houses and his children work for the government. When he tried to return after visiting a friend in Jordan, Alsaedi’s uncle was kicked off the plane.

His uncle is now stuck, alone, with no one in Yemen to go back to. His business, his family, his house, is all in the U.S.

“It’s just heartbreaking,” Alsaedi said. “Getting kicked from your own country that you’ve been trying to build and put effort to upgrade and it just feels like you’re getting kicked from your own home or something. You cannot express it in words.”

Alsaedi said his family is scared, but also surprised and waiting for other people to defend them.

“It’s just disappointing, you know? Everybody who leaves Yemen or any country and comes to the U.S., they have dreams and they just can’t imagine one day that they will be kicked out of this country one day for no reason,” he said.

Uddin said he doesn’t think the ban will keep the country safe, but rather, plays into the extremist’s narrative.

“Extremists are constantly fighting to prove that we’re at war with the United States. You know, ‘they’re against us, they’re our enemies’ and this ban just reinforces what the extremists are fighting for,” Uddin said. “Look at that, they’ll say, ‘they’re banning our people, they’re banning innocent people, they’re bombarding our people.”

The silver lining: what comes next

Haque said the best thing for people to do is to talk to a Muslim and make a friend.

“Don’t think about the religion, focus on the human being,” Haque said. “I know a lot of people who came here from Iraq, Iran, Syria, they came here to be in America. They want their kids to go to school, they want to learn English.”

Samiha Islam, Muslim Student Association president, said Trump’s policies have had inadvertent, but positive effects.

“As much as it’s been a hard few days, it’s also been some of my proudest few days,” Islam said.

Islam said growing up as a Muslim, you are told to stay “under the radar” and “stay out of trouble,” because parents understand their children may not have the same rights as “normal” Americans if they do get into trouble.

She said Trump has given a voice to the Muslim community in an “unprecedented way.”

There are American students who stand in solidarity with the Muslim students at UB.

“We’re supposed to welcome these people with open arms and help them have a better life,” said Jacklyn Denison senior psychology and health and human services major. “Most of them have the same beliefs and values as many of us. They are us, we’re all the same.”

Islam said watching people from all over the world come together to speak in one voice against the Islamophobia, has inspired and motivated a lot of Muslims.

“And that’s really the silver lining, because for years Muslims would pray to not be on the media because if we were it was usually not for a good thing,” Islam said. “But now we’re in the media for something amazing and incredible; vigils, protests, marches, happening across the country, that’s powerful.”

Sarah Crowley is the senior features editor and can be reached at sarah.crowley@ubspectrum.com