Steven Coffed, a sophomore aerospace and mechanical engineering major, has a valedictorian certificate hanging in his bedroom, a mention in a Business First article that named the best scholar athletes in Western New York, a Presidential Scholarship - which is awarded to only 25 of the university's approximately 5,000 incoming freshmen - and multiple other academic honors.

One of his most treasured possessions, however, is a Marvin the Martian watch.

At first glance, the watch could be seen as a subtle but arrogant reference to his success because of its juxtaposition. Marvin is known for continuously failing despite his superior intellect.

But as he sits smiling in his loosely fitting red button-up, it's clear Steven is not a cocky persona. Self-assured, but never cocky. Steven's friends and family laud him for his brilliance but never forget to point at his laidback, amiable personality. His surgical precision when balancing numbers and concepts doesn't outweigh his humanity.

That watch - and the red shirt - also belonged to his father and best friend, Jim Coffed. Jim was a talented engineer with the soul of an artist. He was also an avid bike rider who advocated for bike safety in the Western New York community. This wasn't exactly a hidden hobby, either; Jim rode outfitted with a bright helmet, reflective gear and a safety bar, which was encrypted with quips like "GET OFF THE PHONE" aimed at trailing drivers.

His passing seemed too random for a man who was so passionate and talented - he died from a collision with a garbage truck one summer morning. Even as bright of a character as Steven is, when he reflects on the incident, he often pauses as if struck by the bitter numbness of being blindsided by one of life's cold mechanisms.

A few minutes later, his recollection of his father feels cathartic, in a sense. It's about 9 a.m. on a winter day and he looks re-energized. He's still grieving, but there are too many more worlds to conquer to mourn.

--

As a child in St. Mary's Elementary School, Steven not only showed how smart he was but also a sense of focus and drive that's rare at such an age. The Depew, N.Y., native was always close to his family, but the true answer to why Steven was always so motivated has always remained a mystery to many of his relatives.

"Jim and I never had to push him at all. He was just driven to be the best he could," said Sue Coffed, his mother and a teacher in the Starpoint Central District. "He was very self-motivated, so it wasn't like we had to say, 'Steven, do your homework.'"

Steven's work ethic never waned as the years went by; it grew just like his accolades. He maintained honors from elementary school to junior high, became class president in seventh and eighth grade, developed into a skilled sportsman and grew into an accomplished pianist from when he first started playing the instrument when he was in second grade.

St. Joseph's High School didn't offer Steven much of a challenge, either, judging from the fact that he graduated with an average of over 100. He was also captain of his school's soccer team for two years, a member of the National Honor Society and a key member of the school's jazz band. He got accepted into schools like Notre Dame, Yale and the Eastman School of Music, but chose UB because of the Presidential Scholarship - which covered all UB-related costs.

These are all achievements the average student would boast about, but Steven speaks about them as if they were arbitrary. His motivation is obligatory, though.

"From me being an only child, I saw how much my parents gave me every day," Steven said. "They were super supportive ... giving me rides, paying for me to go to a good high school - all that stuff. It just made sense in my mind to give back to them."

Steven didn't just ride high school off his natural intellect; his work ethic was supreme. It's the type of hard work that requires a student to wake up for school at 6 a.m. after staying up until 2 a.m. to finish homework. One of the highlights of Steven's day was a little nap he caught on the 40-minute bus ride from his house to St. Joe's.

Steven's musical and academic ambitions never overshadowed his approachable personality - laidback, fun-loving, quick-witted. He's what one would consider a "guy's guy," or the type his best friend Aidan Ryan says "you'd want to have when you're in a bind." In short, he doesn't fit into the "nerd" stereotype his certificates would suggest. Nerds don't usually get kicked out of senior trips for bringing alcohol.

His musical taste - which ranges from metal to R&B - may be Steven's most unique trait. His favorite musician is Elvis Costello, which is almost too fitting. The famed songwriter's influence isn't limited to one genre, and Steven's interests aren't just limited to engineering, music and academics. He's an adventure seeker.

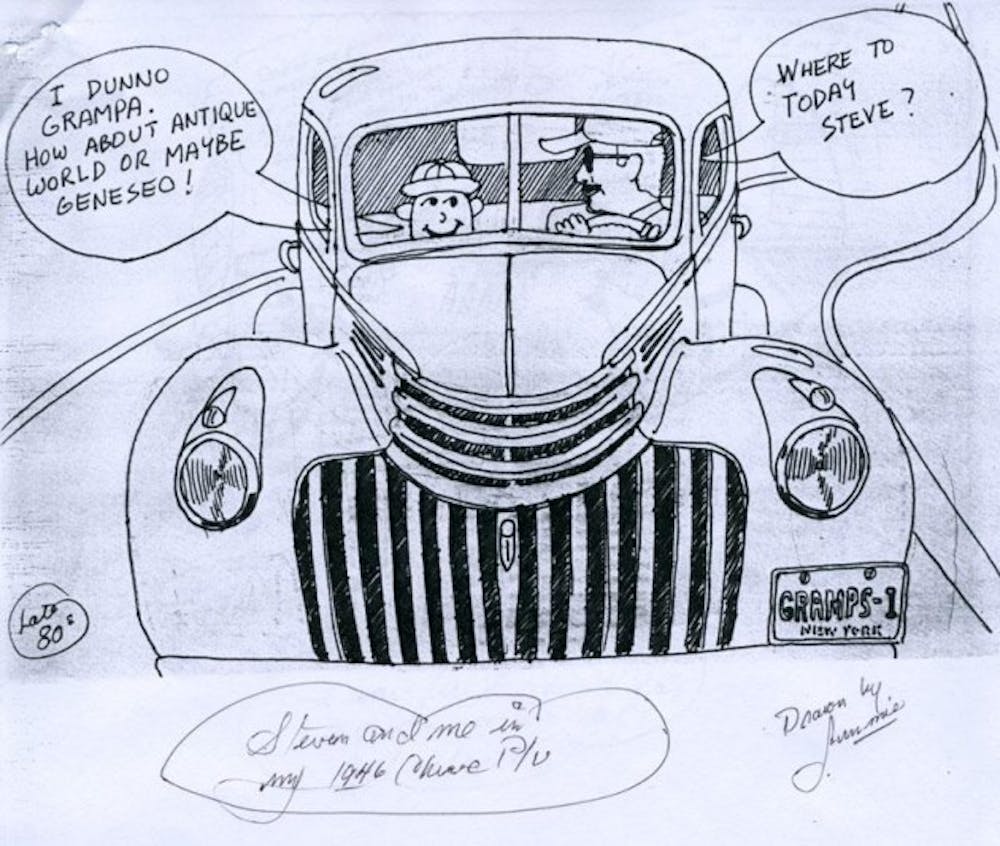

Jim was also an adventure seeker. He was artistically talented as well; Steven played instruments, while Jim drew sketches. Both were naturally intelligent, too. Jim's brother, Mark, and his father, James, both agree he was the smartest one in the family.

Jim was Steven. Steven was Jim.

"He's pretty much a clone," Mark said. "If Jimmy was still around and I introduced you to him today, here's how I'd introduce you to him: 'This is my brother, Jim, he's the nicest and smartest guy I know.' I'd probably say the same thing about Steven."

The father-son duo went everywhere together. Jim's Disney World was Allegheny State Park in New York and his Europe was Redwood National Park in California. Because of Jim, Steven has been going to Allegheny "ever since I was in the womb." Jim would also take his son to air shows, which influenced Steven's love of aerospace engineering.

Jim was a mechanical engineer. After a stint at a company that made windshield wipers, Jim became a design engineer for Greatbatch Medical - a business that specializes in making components for implantable medical devices, such as the pacemaker. He was an engineer by trade but had the soul of an artist, as he'd use his three-dimensional thinking ability to solve problems. The trait was particularly crucial in such a difficult line of work, which created parts upon which people's lives depended. It would take Jim as long as five years to get some of his patents approved.

Perhaps Jim's biggest impact was his love of biking. An avid bicyclist for about 20 years, Jim caught eyes by being the very picture of biking safety. He'd wear so many bright colors that Steven said it looked like as if "he swallowed a neon glow stick." His biking outfit would elicit sympathies from others.

"If you'd go by him on the street, you'd say: 'Look at that homeless guy. Poor fella,'" said Tom Marzano, Jim's supervisor at Greatbatch Medical.

Jim traded in his car for long bike rides to his job in Clarence, N.Y. When he'd return from work, he was ready to tell his family stories about his encounters with drivers while he was riding his bicycle. Jim was adamant about bike safety but never hostile; he traded confrontations for sharp quips to get his point across. His focus seemed necessary judging by the statistics.

"In Erie County, 5 percent of all accidents include bicycles and pedestrians," Justin Booth of Go Bike Buffalo told WIVB. "They represent 31 percent of all injuries and fatalities in the region."

--

In the summer of 2012, Steven was used to his father waking him up around 7 a.m. to say goodbye before he went off on his bike to go to work. Steven would then sleep until about 11:30 a.m. before he began his day.

July 2 started out similarly with a goodbye from his dad around the same time - only this time, he woke up 20 minutes later to his mother's shrieks. The police showed up at the front door.

Jim had died. He was 52.

Jim's father, James, who spent decades as an accident investigator, recollected the trauma with a Spectrum reporter eight months later. He's covered all kinds of accidents throughout the years but said in a suddenly world-weary tone that nothing could prepare him for this. His clear eyes didn't symbolize decades'-old wisdom but revealed a deep-seeded wound that still bleeds.

"The day before he died, he came over to my grandparents' house and drew a picture of what the design [of his latest work at Greatbatch Medical] was," Steven said. "My grandfather has a hard time looking at it, because it brings back a lot of emotion."

Jim was riding down Walden Avenue when a dump truck suddenly turned right, resulting in the life-ending collision. Steven didn't find out the details until days after. He was still in shock over losing his best friend because of a random instance.

"They were close, real close," James said. "If you could think of the closest person to a parent - mother or father - that would be the type of relationship."

What particularly haunt Steven are the green bike and the helmet in which his father was killed. Both are sitting in Steven's house - undamaged.

Sue received Jim's last approved patent the day after his death.

"The only thing missing is him," Steven said.

Then came the mourning; then came the diagnosis - Steven found out he had mononucleosis(the kissing disease) a day after his father's death; then the comfort of his girlfriend, Jessica Wojcinski, who returned from a trip to Chicago for the funeral; then the funeral, which was attended by hundreds of people whom he had affected by his personality, mechanical work and dedication to bike safety.

Instead of a prayer, Steven opted to put lyrics from Elvis Costello's "(What's So Funny 'Bout) Peace, Love, and Understanding" on his father's prayer card for the funeral. Jim would've liked that.

This all happened days before Steven was supposed to go on his anticipated trip to Germany with Ryan. Steven was undecided on whether he was still going to go, but he only thought of what his father would advise him to do in such a situation. That would be to go, because Steven believed Jim lived every day to the fullest.

While Germany provided a refreshing change of scenery, the trip still proved to be a painful one.

"It was not ideal," Steven said. "Every day you wake up, it's like you don't want to get out of bed. You don't want to move. You don't believe that that's happened. There are still days where I wake up and I still have some dream where I'm out biking with him. Then you wake up and forget that he's gone."

The world didn't stop, though. School was but a few weeks away when he returned from Germany.

--

Aerospace and mechanical engineering are generally considered two of UB's hardest programs.

Steven decided to take 24 credit hours last semester with courses from those programs, which was a decision he would come to regret.

As expected, the workload proved to both emotionally and physically taxing for the sophomore, who lives in Greiner Hall and would often call his mother for support.

"I didn't realize that he was taking that many credit hours, and it sickened me when I found out. His comment was that I think I needed to be occupied," Sue said. "The thought process behind it was bury yourself in your schoolwork and you won't think so much about your dad. I didn't find out until November he was taking that many credit courses."

He didn't go through the semester with the same self-assuredness he had in high school. This made the news he received that one day in his work office after the end of the semester all the more surprising.

He found out he had gotten a 4.0 GPA. The heartbreak and tribulations he'd endured had been worth it.

Steven left his job at the UBIT office, went to Baird Point and cried. He had succeeded once again.

"I told people in my family and they were like: 'Don't take so many credits,'" Steven said. "People were happy for me, but they knew how much work went into that, and they knew a lot of it had to do with this need to prove myself and that I could keep going on. On one hand, it was good; on the other hand, it was destructive at times."

--

Steven is now taking 15 credits. His semester isn't any easier, though; he makes it his mission to find time for his family in addition to keeping up with his courses and continuing to play keyboard. Jim's passing has convinced him life is too random to skip out on spending time with loved ones.

Steven's also starting to fit into his dad's clothing, which he said he wears more now. Although he still misses his dad, the sophomore puts everything into perspective. Living is painful, but it can be worse. It can also get better.

He had the honor of summarizing that philosophy - moving forward and appreciating the now - when he delivered his father's eulogy:

"I said how he was the kind of man who lived every day like it was his last. He was always spending time with family or saying, 'Hey, I have a day off. I know you have some homework and probably got to get stuff done, but why don't you and I go to Allegheny,' or, 'Why don't you and I go out and catch a movie?' He was doing that not only for me but for everybody. As hard as it is for me to see him go, I don't think that he lived with any regrets. I hope that in his memory and for his sake, other people will live that way, as well, and recognize that each day is one to be lived to the fullest. While I mourn for the loss of my father, it was my best friend I was going to miss.

"I said good night and told him how much I loved him."

He can always see his father when he looks into the Marvin the Martian watch.

Email: features@ubspectrum.com