A short, shrill beep pierced through the silent room. The audience watched with bated breaths as the next test ? meant to simulate the 2011 Christchurch earthquake with a magnitude of 6.3 ? began.

Violent tremors, generated by an earthquake shake table, rocked both walls from side to side. A few seconds later, the left wall couldn't stand. Its upper part, also known as the parapet, fell with a resounding clank onto the steel structure between the two walls. It leaned limp while the parapet of the right wall became slightly displaced from the wall's lower part moments later.

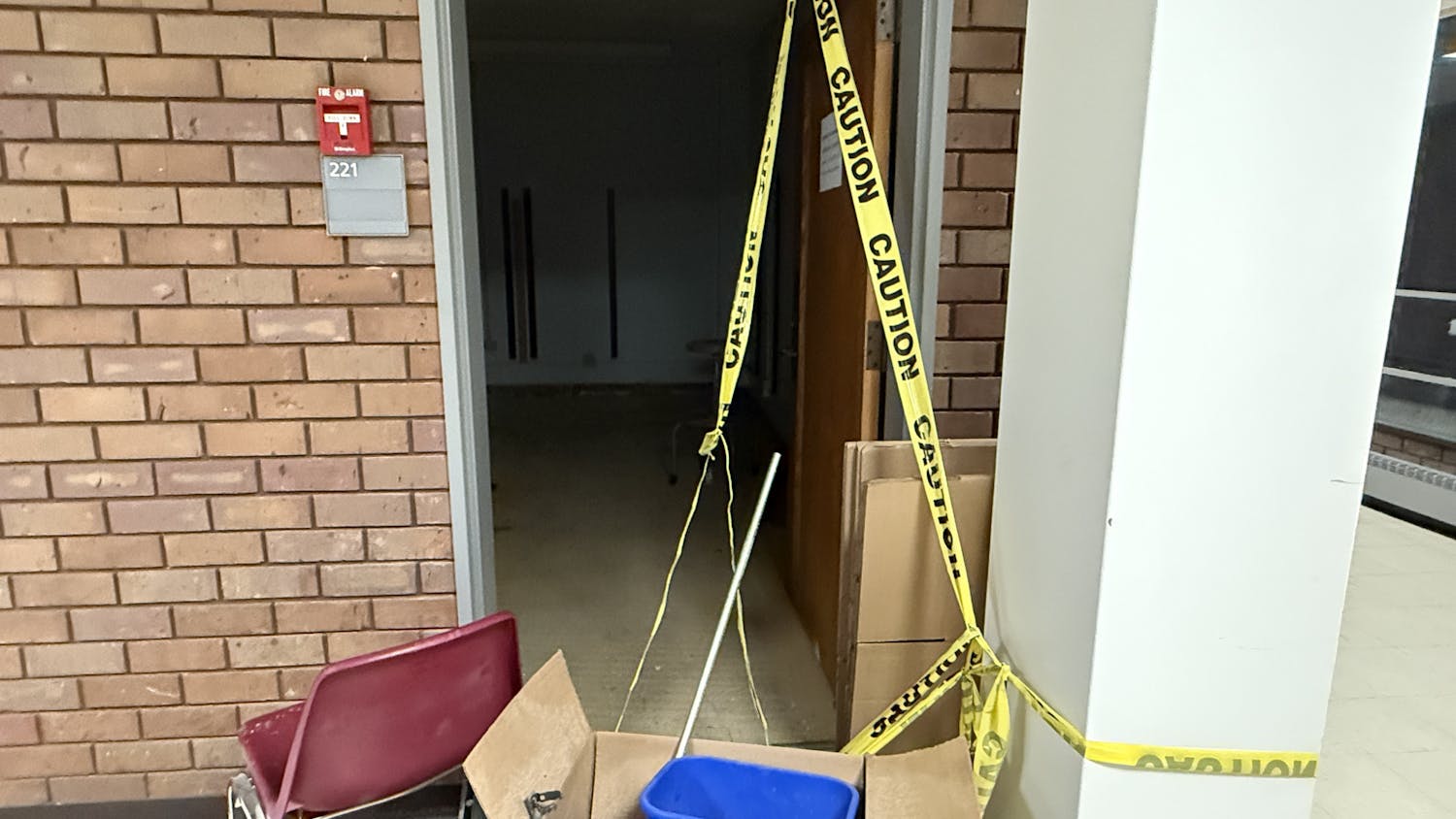

Last Tuesday, UB's Structural Engineering and Earthquake Simulation Laboratory (SEESL) simulated an earthquake inside Ketter Hall. It was part of an experiment by UB researchers to study how unreinforced masonry buildings in New York City, specifically brownstones, would fare during an earthquake.

"[The experiment] was pretty interesting and exciting because you see the walls falling down," said Ciara Olea, a senior civil engineering major who witnessed the experiment. "I was excited because I've never seen anything like it before."

The experiment marks the first time researchers are studying the seismic behavior of unreinforced masonry walls found on the East Coast.

A shake table was used to produce intense ground motions.

The two walls in the experiment represent the unreinforced masonry structures in New York City. They were made using 100-year-old bricks and specially made mortar.

The initial tests simulated the 2011 Virginia earthquake with a magnitude of 5.8 and later tests simulated the Christchurch earthquake that shook New Zealand the same year. Experimental results will help validate computer simulations used to evaluate seismic risks such as casualties and economic loss, according to the program's handout.

"Our goal is ultimately to understand the risk posed by unreinforced masonry buildings in NYC," said Andrew Whittaker, a researcher involved in the project, professor and chair of the Department of Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering (CSEE) and director of the Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering Research (MCEER).

The work performed at MCEER represents the first two steps in a multi-step process to assess earthquake risk and earthquake vulnerability on unreinforced masonry buildings in the city, according to Whittaker.

There are no "reliable computational tools" to predict how such unreinforced masonry buildings are going to behave during an earthquake, according to Juan Aleman, a Fulbright scholar and Ph.D. candidate in civil, structural and environmental engineering.

Yet, unreinforced masonry buildings make up 80 percent of construction in New York City, researchers said.

Brownstones, common in the city, were popularized in the late 1800s to early 1900s and many are more than a century old. Age, combined with wear and tear, makes these constructions potentially hazardous.

"Some older, unreinforced masonry buildings in New York City are collapsing just due to their own weight or fires," Gilberto Mosqueda, faculty adviser of the research team and associate professor in the Department of Structural Engineering at the University of California at San Diego, told UB News Center.

Whittaker is also concerned about the safety of these buildings.

"The past experience is that they are vulnerable to earthquakes and vulnerable in the sense that they collapse and kill people," he said.

Earthquakes with a magnitude of five and higher are uncommon in New York but are possible. Even a moderate earthquake could be disastrous in the city because of dense population and hectic commercial activities, UB researchers said.

In the final test, the parapet of the left wall fell.

If this simulation actually occurred in the city, "[It] could have probably killed a person. If someone was walking on the street, the parapet would have fallen down [on him or her]," Maikol Del Carpio, a research assistant and Ph.D. candidate in civil engineering, told YNN.Aleman has personal experience with earthquakes. He is from Nicaragua, part of the infamous pacific ring of fire, where seismic activities are common.

"My full house was shaking like crazy; it was amazing [and] really scary," Aleman said about a 5.0 earthquake near his home in 2000. "My house was not damaged, but other houses almost collapsed."

To Aleman, the project was "really rewarding." He feels better prepared to help in the engineering community in New York as well as his native home.

UB has a "pretty unique combination" of "strong faculty" and "world-class facility," according to Aleman.

Olea thinks the simulations could attract incoming students.

The entire experiment lasted a few hours, but the walls collapsed in a few seconds. For four years, the team did experiments and scoured New York for appropriate materials to build the two walls. The International Masonry Institute donated the bricks.

Apart from Whittaker, Mosqueda and Aleman, project participants also include Amjad Aref, professor of structural and earthquake engineering. The research is a joint effort with the Structural Engineers Association of New York (SEAoNY) and the International Masonry Institute (IMI).

The research team will be doing extensive data analysis as a follow-up to the simulations. Whittaker said the team hopes to obtain funding from the federal government in order to "quantify the risk and exposure that folks have in New York City to earthquakes."

Email: news@ubspectrum.com