The Buffalo community knew Torin Finver as a “driven” man and an expert in addiction medicine, who for the past four years forged unique bonds with patients by making them feel he understood their struggles.

He helped hundreds of patients as a doctor at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and at rehabilitation groups at Horizon Health.

That’s why the medical community was shocked on Dec. 17 when federal agents charged Finver with two counts of importing cocaine and heroin.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers and postal inspectors located and intercepted four suspicious packages of heroin and cocaine addressed to Finver’s home between Nov. 21 and Dec. 15. One package contained 3 grams of cocaine; others contained undisclosed amounts of heroin and cocaine, police said. Police then did a “controlled delivery” of a fake substance on Dec. 17. Finver claimed the drugs were for personal use, according to U.S. Attorney John P. Kennedy's office.

The drug charges carry a maximum penalty of $1 million and 20 years in prison.

UB fired Finver on Dec. 23 and he forfeited his medical license.

Torin Finver, a former UB doctor, assisted patients around the Buffalo area with drug addiction. In December, federal agents charged Finver with two counts of importing drugs.

Finver’s UB colleagues declined to talk about his legal case, but said addiction in the medical field is not uncommon. Often doctors who become addicted do not seek help for fear of losing their medical licenses.

At least one in 10 health care professionals misuse substances, such as opioids during their lifetime, research by the Butler Center for Research in Minnesota shows. Doctors who have surrendered licenses in New York due to addiction since June 20, 1997 can have them restored three years later, according to New York State Department of Health spokesperson JP O’Hare.

Finver’s former colleague Richard Blondell, a family medicine professor and the JSMBS’ vice chair for addiction medicine, said the university should treat Finver’s relapse as an illness.

“In general, how should a university respond to anybody who is sick? We have a doctor who has a chronic relapsing disease and it got the better of him,” Blondell said.

“Do we run away from him? Do we hide? Do we pretend it doesn't exist? We would not do that with anybody else.”

A community in shock

James Simon remembers the day Finver changed his life.

And it was the only time they ever met.

Simon, a Buffalo resident, attended six or seven other rehabilitation centers before arriving at Horizon a few years ago.

Finver was running a group session with patients. He was the only doctor Simon had ever seen run one; usually psychiatrists ran them.

Someone suggested a patient had an “addictive personality” and the counselor in the session agreed. Finver knew they were both wrong, Simon said.

“[Finver] came in and just destroyed all of them with medical facts on how there’s no such thing as an addictive personality,” Simon said. “He was running through pharmacologically what happens in the brain. He broke down the limbic system and the prefrontal lobe and how the damage is between the two. And then he literally tied it all up in a nice neat little bow … He hinted that basically the solution was spiritual in nature.”

Simon said Finver led him to trust groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous.

“This was five years ago and I remember it. It changed me,” Simon said. “There was only a couple of groups I paid attention in and he was one of them.”

Simon said Finver’s perspective on addiction and ability to communicate medical information worked for a lot of community members.

“I never knew he [used drugs], but I kind of knew he was on a level. He had a way of really knowing how to meet people where they really are,” Simon said.

He called him an “enigma,” saying “most people don’t make it through with the level of success that he has. They don’t have that unique perspective of knowing it intimately. It’s like a perfect storm. How do you create a guy like that? You can’t. He’s invaluable. He’s f–––––g priceless.”

Paige Prentice, the senior vice president of operations at Horizon, worked closely with Finver as a supervisor and said she saw no signs Finver was struggling with addiction.

“Torin was a driven man, especially when it comes to addiction and addiction medicine. He wanted to make sure people were taken care of ... ,” Prentice said. “He was really just on a mission to make sure the field could advance and people would get the treatment they need.”

She said this wasn’t the first time a Horizon employee had dealt with addiction.

“I think [addiction in the medical field] is more common than we would like to admit or know about,” Prentice said. “I wouldn’t say it’s rampant, but I do think it’s more common than we would want to think about.”

Finver’s coworkers at UB were also upset and surprised by the news of his arrest.

Megan Veirs, UBMD Marketing Communication Specialist, called Finver an “advocate and a leading force in the community for helping those with the disease of addiction with their recovery.”

Veirs said UBMD was “collectively saddened to hear about the charges.”

Blondell, who worked alongside Finver, said the opioid epidemic has seen drastic changes during his time as a physician.

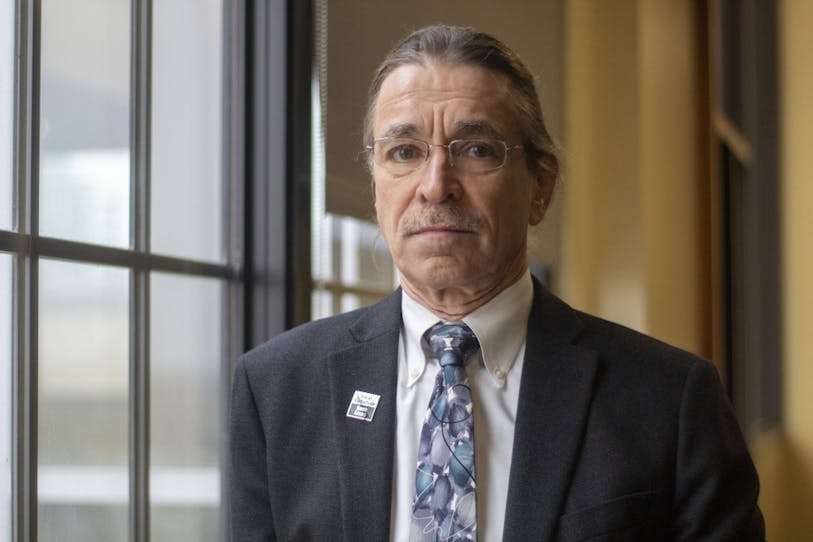

Finver’s former colleague Richard Blondell is a family medicine professor and the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences’ vice chair for addiction medicine. Blondell, who worked with Finver, said the university should treat Finver’s relapse as an illness.

He said typical patients in the detox unit were older people battling drug and alcohol addictions when he began working as a physician. But this shifted, he said, with greater numbers of young adults “who come from good socioeconomic backgrounds” requiring rehab services.

“So what's different about it is we've gone from older [people from disadvantaged backgrounds injecting] heroin from disadvantaged backgrounds, to your peers,” Blondell said.

Finver did not respond to The Spectrum’s numerous attempts to reach him through colleagues and on Facebook.

Addiction by the numbers

Roughly 11.4 million people have misused opioids in the past year, according to 2017 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administrations data.

That’s enough people to fill UB Stadium 393 times.

Still, that’s fewer than it was a few years ago when the opioid crisis was at its zenith.

But, even as national numbers of opioid-addicted patients decrease, the amount of opioid misuse among doctors like Finver remains stable, according to a number of national studies.

In Erie County, overdose deaths increased from 101 in 2013 to 301 in 2016. But deaths have decreased in the past two years. There were 148 confirmed opioid overdose deaths in Erie County last year, as of Jan. 24, according to Erie County public information officer Daniel Meyer. Meyer said that there have been 54 suspected opioid overdose deaths in 2018 –– awaiting final autopsy results –– as of Jan. 24.

Between 10 and 15 percent of medical professionals will “misuse substances during their lifetime,” according to the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation for addiction treatment. The foundation reports that prescription “drug abuse” and addiction rates are five times higher among physicians than use among the general population.

Finding help

UB and Buffalo’s Horizon rehabilitation center offer confidential employee addiction assistance.

Susan Bagdasarian, a UB EAP consultant, said UB employees have contacted her office to handle their own drug and alcohol addiction and seeking help in living with addicted family members. Her office helps connect employees with groups like Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous and assures employees of confidentiality, she said.

SAMHSA also offers guides and services for getting treatment, including a treatment locator available on its website. There are 45 locations within a 15-mile radius of North Campus which offer substance abuse services, according to the map. SAMHSA also has a guide titled “Finding Quality Treatment for Substance Use Disorders” online to help people evaluate treatment options.

Addiction, Prentice said, can affect anyone, and everyone has to be vigilant and ready to help.

“There’s still a certain level of disbelief or shock or whatever that a medical professional would be struggling with this,” Prentice said. “To that I just say, medical professionals are just people.”

She added, “Torin, at the end of the day, is just another guy. He happened to be a doctor and he happened to specialize in treating addiction but that doesn’t mean he’s not going to have problems himself.”

If you or someone you know is addicted to substances such as opioids, call the 24/7 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration hotline at 1-800-662-HELP. SAMHSA’s treatment locator is available on its website.

Benjamin Blanchet, Brenton J. Blanchet and Jacklyn Walters are editors and can be reached at news@ubspectrum.com and on Twitter @BenjaminUBSpec @BrentBlanchSpec and @JacklynUBSpec.

Benjamin Blanchet is the senior engagement editor for The Spectrum. His words have been seen in The Buffalo News (Gusto) and The Sun newspapers of Western New York. Loves cryptoquip and double-doubles.

Brenton J. Blanchet is the 2019-20 editor-in-chief of The Spectrum. His work has appeared in Billboard, Clash Magazine, DJBooth, PopCrush, The Face and more. Ask him about Mariah Carey.

Jacklyn Walters is a senior communication major and The Spectrum's managing editor. She enjoys bringing up politics at the dinner table and seeing dogs on campus.