Kelsey Barbour was radioactive for 48 hours.

Quarantined in her bedroom and allowed minimal human contact, Barbour sat docile as radioactive iodine coursed through her body. The treatment had one mission: Destroy any lingering thyroid cancer cells.

It was Oct. 2011. Three months prior, Barbour was diagnosed with cancer. In Aug. 2011, doctors removed her entire thyroid. A 1 1/2-inch scar stretched across the base of her neck.

That fall, Barbour had to face the treatment alone. Her body was giving off radiation; even contact with her mother had to be limited. Barbour only saw her briefly to receive meals. Her younger brother, who couldn't be exposed to the radiation because he was under 18, had to stay with a friend.

But as Barbour will attest, she was only alone in the physical sense.

Stuck in the confines of her room, Barbour Skyped with her second family: UB's swim team. She watched the men's and women's teams on her illuminated computer screen as they moved crisply through the water - Barbour isn't one to miss practice.

After facing isolation, she was thrilled to reconnect with her teammates. Her spirits were lifted, and she was reminded that she had everyone behind her.

It would be another eight months and a round of radioactive treatment before Barbour would know she was officially in remission.

Once Barbour got the official word, she felt the same rush she does when she tears through the water and is the first person to slam the touchpad and win a race by a fingertip. In that moment in the pool, it is Barbour's hard work that exudes. In beating cancer, it was her strength that shone through.

Barbour, now a junior health and human services major and member of the women's swim team, has been cancer-free since June 2012. At 19, she faced her own mortality. And now, about a month before her 21st birthday, her scar - once a visible talking point - has mostly faded into her olive complexion.

Barbour isn't one to talk about her bout with cancer, but she is one to take action. Since her diagnosis,Barbour has become a member of UB Against Cancer (UBAC) and an executive board member of UB's Relay for Life planning committee. She has also created her own fundraiser with members of her swim team called "Hope Floats." Through these initiatives, she has helped raise thousands of dollars for cancer research.

But Barbour won't stop there.

For her, fundraising for cancer research isn't just a hobby or a side project. It's become her life path and after-college career plan. In cancer, Barbour found her mission: to help raise money so every cancer patient can be as lucky as she was.

***

Her friends, family and head coach agree: The word that best describes Barbour is resilient.

You can't see her thick skin through her bright eyes and big smile. But behind her sweet, bubbly voice and emanating compassion is a girl who never allowed cancer to stand in the way of life. Admittedly stubborn, Barbour - complete with an athletic frame that clearly belongs to a swimmer of 12 years - planned to miss the least amount of school possible in handling surgeries and treatments. She didn't want to fall behind.

Three weeks after she had her thyroid removed, she was back at UB ready to start her sophomore year.

"One of the things I told her up front was: 'I don't want you to play the victim,'" said Andy Bashor, the head coach of the swim team. "You play the victim, you've lost. You have to look at this [as] happening for a reason, use this as a positive to help shape you, because this is who you are and I think that can be a very empowering thing when you own it."

Barbour has used cancer for just that - empowerment. Barbour doesn't play the victim and pushes so others can be granted the same opportunity at life. "I did have cancer, but that didn't define who I was," she explained. "That's what I really want for other people."

So she works. Hard. Today, she carries around a packed planner bursting with "to-do lists" scribbled on sticky notes. One of the best gifts she can get from one of her roommates is a new pack of the brightly colored, lined adhesive bits of paper, she laughs.

She manages to balance a full-time course load with swim practices and event planning for fundraisers. This season, she swam the best time for the 100-yard breaststroke on her team. "It's my race," she confirms. "It's more of an awkward stroke," she jokes, explaining how her legs have to move like a frog's as she sweeps her arms in and out.

She isn't the most competitive person on the team and while the edge to win does find her at times, she also is just happy doing what she loves with the team she loves.

What really gets Barbour motivated is the battle against cancer. She wants cancer patients to receive the treatments they need to survive like she did.It fuels her passion.

Now in remission for about 11 months, Barbour stands to evaluate life from a perspective most college students don't have. Barbour's eyes - which are often hidden behind the cool, slick-blue plastic of her swim goggles - can bring the "big picture of life" into focus.

But she started her freshman year like most new students - looking to find her niche on campus. She was excited for a new surge of independence and happy to have a built-in network of friends on the swim team. She was a comfortable distance from her hometown of Clifton Park, just outside Albany, and she was the third Barbour daughter to make her way to UB's campus.

She first noticed an unsettling lump on the base of her neck when she was doing her makeup in a magnifying mirror during that first year of college. She didn't think much of it. She didn't want to overreact.

But over the course of her freshman year, she noticed the lump getting bigger and eventually brought it to the attention of doctors, who come to the trainers' office in Alumni Arena.

Lynlee Barbour, Barbour's sister and a public healthmaster's student at UB, said when Barbour tilted her head back, the lump looked like "a second Adam's apple."

The trip to the doctors in Alumni began the three-month journey that would eventually end with a cancer diagnosis - something Barbour never expected.

Doctors threw the word "cancer" around but with the suggested possibility came reassurances it was highly unlikely.

In June 2011, she had abiopsy taken of her thyroid cells to test for cancer; the results were inconclusive. In July, she had a part of her thyroid removed so a diagnosis could be made.

From the original test, doctors "didn't think it looked like cancer," according to Lynlee. "When they went in a second time to take part of her thyroid out, they didn't expect to find the cancer cells," she said.

On July 20, 2011, Barbour and her mother were on two separate ends of their home's landline to speak to the surgeon together on the phone.

The verdict: Cancer.

The plan: Surgery. School. Treatment.

"It was a lot of medical talk that was over my head and I didn't care to listen," Barbour said. She didn't absorb the details but grasped what she and her family needed to do. "We figured we'd take it day to day."

After a second surgery in the first week of August, in which surgeons removed what remained of her thyroid, Barbour came back to UB with a new scar and plans to take on further treatment in October. But when others probed her at athletic orientation about the source of her new scar, her answer was simply: "Oh, I just had surgery."

Barbour, aware cancer is a "buzzword," didn't want to make anyone uncomfortable. She wanted to be sensitive to others' feelings. "I know how trying to react to something like that can be," she said.

Katelyn Grimm, one of Barbour's best friends, said Barbour never plays "the cancer card."

"She doesn't take it as 'woe is me,'" Grimm added.

But Barbour didn't shroud her cancer as some big, scary secret. Her two best friends, roommates and swim team members, Grimm, a junior communication major, and Taylor Lansing, a junior psychology major, knew all the information Barbour knew related to her illness.

"If it was a shock to her, then it was a shock to us," Grimm explained.

But the situation was no different from how the three girls tackle any part of life. The close-knit trio is constantly in each other's business, but they wouldn't have it any other way.

The two best friends helped Barbour through the taxing time leading up to her first radioactive iodine treatment.

Thyroid cancer cells can travel throughout the body and the thyroid gland absorbs most of the iodine in blood. By taking a radioactive iodine pill, Barbour made her iodine cells radioactive. Her thyroid cells then absorbed the radioactive iodine cells, which aimed to destroy any remaining cancer cells. Her body was also scanned to see if any cancer cells lingered.

In order for the radioactive iodine to be effective, Barbour had to go on a strict low-sodium, low-iodine diet and stop taking her artificial thyroid medication.

Because Barbour no longer had a thyroid, the gland responsible for regulating hormones and the body's energy use, she began taking a pill to keep her body balanced. She was mandated to take the pill every day - except for the two weeks that led up to her radioactive iodine therapy.

Without the medication, Barbour was continually fatigued. But she didn't let the exhaustion win.

She never missed practice.

"Nothing is going to stop Kelsey from doing what she wants to do," Grimm said.

While the surgeries to remove Barbour's thyroid kept her out of the water that summer, the only time she truly took off from the swim team was the week and a half she spent back at home getting the radioactive iodine therapy.

And though the thought of having to redshirt her sophomore year crept into her mind,Barbour kept swimming.

"I was already that much further behind than I normally was," she said. "So it did cross my mind that I wasn't going to able to swim that year."

But she pushed on and wound up only sitting out the first five meets of the season and took two weeks off practice.

When she swam in the Mid-American Conference Championship meet in the 2011-12 season, she set three lifetime-bests.

"She didn't allow [cancer] to define her," Bashor said. "In a way, it kind of gave her extra motivation to not let cancer defeat her and take away from her success."

Cancer-free, Barbour was interested in taking on more than just swimming. She wanted to give back.

It started in 2011 with the idea for Hope Floats, a charity led by Barbour, Grimm and Lansing that involved the men's and women's swim teams. In Jan. 2012, the event - which came to fruition and was held during a swim meet - raised $9,400for the American Cancer Society. The swim team still proudly sports its royal blue Hope Floats swim caps and T-shirts. It was a lot for three college sophomores to organize, but the trio was determined to do it independently and make an impact.

"What I really loved about it is that it was never about [Barbour]," Grimm beamed."It wasn't about that she had cancer; it was just about this has come into her life, and so she wants to give back and do something."

Hope Floats was just the push off. This year, Barbour became an e-board member of UB's Relay for Life planning committee and heavily involved in UB Against Cancer as a whole.

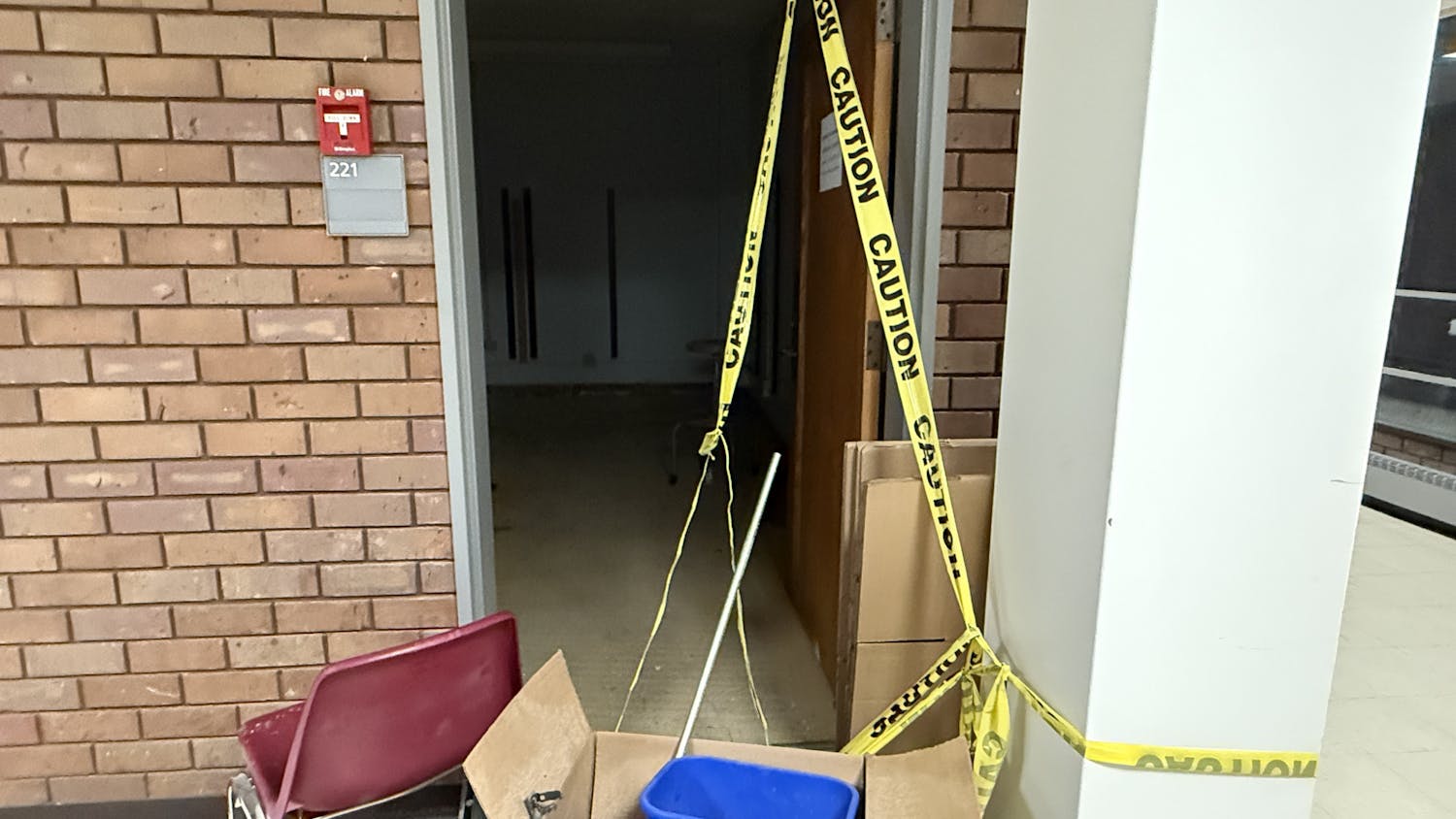

On April 12, 2013, Barbour stood with her brown hair tucked under a black baseball cap, adorned with pins and the Relay for Life logo. She was serving up barbecued chicken - Hope Floats took on a new life as a chicken barbecue, hosted in Alumni Arena before UB's Relay for Life, an event that raises money for cancer research.

A year before, Barbour's role in Relay wasn't behind the scenes, but center stage. Then, eight months past her diagnosis, Barbour was Relay's student survivor speaker. A few things were different then - not only was she donning blonde hair, but she was also a different major with a different career in mind.

Barbour entered UB as an exercise science major and dabbled in speech and hearing before settling into her current major, health and human services. Barbour found her life's direction after she started getting more involved in not-for-profit fundraising, like Relay for Life and UBAC.

Over 1,200 participants piled into Alumni Arena for Relay this year. The theme was "Wish Upon a Cure," a play on Disney - iconic songs suiting the theme were the backdrop to a night of solidarity and remembrance in the fight against cancer.

Barbour's perspective was different from what it was when she attended Relay in April 2012. She wasn't mentally rehearsing a speech, but studying the mechanics of the night. Since Sept. 2012, she and the other committee members toiled to ensure the evening ran smoothly and everything was set in its proper place.

In her e-board position - the event chair of mission, which was created with her in mind - she was responsible for reminding everyone the bigger purpose of that evening.

"We just remembered this isn't about us," Barbour said. "It's about everyone there and anyone who has been touched by cancer."

Barbour - who was so caught up in making sure everyone else was where they needed to be - forgot to sign up to be a part of the event's survivor lap. She put so much of herself into organizing the event that she "just kind of forgot about me being involved in the survivor part of it," she said.

Barbour never makes it about her but the thousands of people she knows she's helping. Even if planning for Relay and homework took over the majority of her time, Barbour always made it work - even if it meant swimming like a zombie at 6 a.m. practice.

This year, UBAC - under which Relay for Life operates- raised about $64,000, according to Julie Smith, the organization's adviser.

Barbour had a large role in raising that money and has been vital to the organization's success, according to Smith. "She's modeling the way," she added.

The fraternities and sororities from the Inter Greek Council raised more money for Relay than in years past, according to Smith. "They saw [Barbour's] passion and they fed off of it," she said.

At the end of her senior year in 2014, Barbour will hang up her swim cap and goggles to focus on her future in raising money for cancer research. She wants to study in a graduate school program for public health and is interning at the American Cancer Society this summer.

In five years, she hopes to be doing the same kind of event planning she does now, but on an even bigger scale.

"Sometimes, I beat myself up because the reason I got involved is because it touched me personally," Barbour said.

She tells herself she shouldn't have gotten involved just for that reason, but remembers everyone has his or her own reasons for becoming an advocate, for fighting the disease and for working tirelessly to help those affected.

It has become a part of her teammates' lives, too. Grimm and Lansing are already excitedly discussing next year's Hope Floats event - a possible 5K run.

Barbour is left humbled and thankful for support, love and volunteering she has seen the people in her life provide, especially her teammates. To them, she feels indebted.

"Things happen in life that set you on a certain path," she added.

Cancer helped her find that path.

Email: news@ubspectrum.com