Quiet contemplation fills the room as visitors study the paintings, prose and poetry on the walls made in homage to the humanity of the people who lost their lives during the May 14 Tops shooting and the difficult healing that the people who survive them endure.

Julia Bottoms’ paintings hold these people within the raw, exposed canvases. A woman holds a baby upright as she touches her forehead onto his, about to kiss his cheek. A couple dances together, content in a world just for the two of them. Two brothers embrace and do not let go.

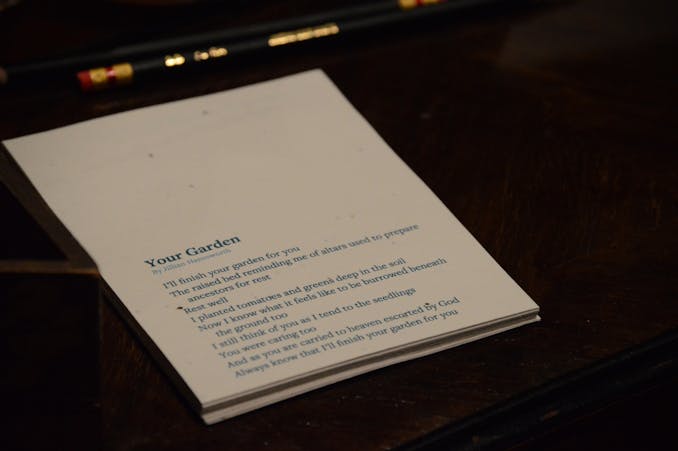

Former Buffalo Poet Laureate Jillian Hanesworth’s poems are scattered throughout the room. One sits on a dresser and acts as a promise to a loved one who was “carried to heaven escorted by God” that the garden the person left behind will be finished. Another, adorning a wall, expresses the author’s righteous anger over the attack: “No speech from the top of the mountain protected the people in the valley.”

The poem "Your Garden" was part of the "Before and After Again" exhibit.

Tiffany Gaines’ prose celebrates each resident’s name and the light they brought to the Buffalo community. It highlights each individual’s best qualities, honoring “the lessons of love found in the lives of the 10 ancestors.”

The “Before and After Again” exhibit is not intended to fit a single description: it should not be treated as just a memorial for the 10 residents, nor is it just meant to be a call to end gun violence. At its core, the exhibit is an open dialogue surrounding the communal grief and sorrow the tragedy caused. It’s a chance to confront racism and its capacity to violently inflict trauma on communities of color.

Befitting its intentions, the opening on March 8 was commemorated with a conversation with the artists and three of the residents’ family members: Garnell Whitfield (Ruth Whitfield’s son), Mark Talley (Geraldine Talley’s son) and Ebony White (Hayward Patterson’s niece). The panel was meant to give surviving family members and East Side residents a space to share what happened on their own terms.

“We didn’t have a chance to breathe,” Hanesworth said. “A lot of us had microphones put in front of our faces the morning after the most painful thing to ever happen in our community… Throughout the process of writing, all of these pieces are really letting families inform the words.”

The family members saw the exhibit as an opportunity to continue their loved ones’ legacy.

“I’m going to speak for my mother who can’t speak for herself,” Whitfield said. “For the others that lost their lives, and for my family, and for my community… It’s my duty to make sure people are aware of what’s going on here and to shine a light on it, not just to bring attention to it.”

The panel was also an opportunity for family members to discuss the artwork on display with the artists. White’s first reaction to Bottoms’ portrait of her — titled “Lily of the Valley” — was surprise that her hands were visible. In the painting, White holds a delicate lily in her hands, looking down at it.

“I refer to my hands as hard-working, and I believe my hands carry generations of women,” White said. “Wow, she captured [and] seen what was on the inside, that it was hard. It’s still hard, but beautiful things are blossoming.”

“I saw a beauty with that,” Bottoms responded, “I saw beauty and your vulnerability. I think now that it’s unpacking it and taking something out; hearing what it means to somebody else new to me in that space. I found it challenging, healing.”

Remembering the people who died is only the beginning. The dialogue is the first step to ensuring that they did not die in vain.

Talley’s painting, titled “Mementos,” was the last one submitted for the exhibit. In it, he boldly stares at the camera, holding a gold lion taken from his mother’s mantle. His eyes silently ask the audience for a response: What will they do about everything that happened?

“I would love for everybody just to close their eyes [and] picture the person who you love most,” Talley said. “Picture a shotgun blowing their head off.”

While the exhibit displays the East Side’s resilience, Gaines says the community should also be defined by its capacity for love and humanity.

“I love that we are beautiful just for being here, in honoring our humanity, in honoring the fact that we are alive,” Gaines said. “Even the smallest ways that we can be mindful and how we show love to ourselves, to each other, to our community… even our enemies. That’s how we make a difference. That’s how we make the change we want to see.”

The exhibit is open at the Buffalo AKG Museum until Sept. 30, 2024.

Mylien Lai is an assistant arts editor at the Spectrum and can be reached at mylien.lai@ubspectrum.com

Mylien Lai is the senior news editor at The Spectrum. Outside of getting lost in Buffalo, she enjoys practicing the piano and being a bean plant mom. She can be found at @my_my_my_myliennnn on Instagram.