Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced on Friday she was reversing Obama-era campus sexual assault policies.

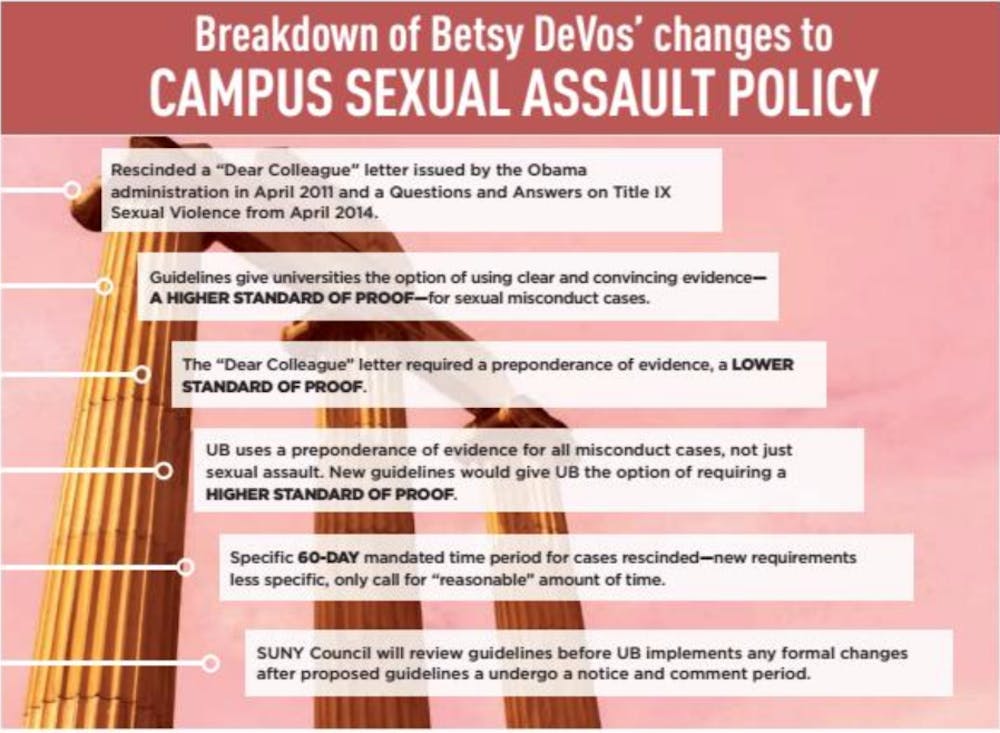

As part of the changes, DeVos rescinded a “Dear Colleague” letter issued by the Obama administration in April 2011 and a Questions and Answers on Title IX Sexual Violence from April 2014. The documents were withdrawn because they did not adhere to notice and comment period requirements and created a system that “lacked basic elements of due process and failed to ensure fundamental fairness,” according to a statement issued by the Department of Education.

The department is working to create a more formal replacement for the Obama-era guidelines after a notice and comment period, which gives stakeholders and members of the public the opportunity to weigh-in on the proposed changes. In the meantime, the Department of Education is giving universities the option to use a higher standard of proof in sexual misconduct cases.

SUNY Council is going to analyze the proposed mandates and issue guidance to campuses accordingly, according to Sharon Nolan-Weiss, UB’s Director of Equity and Inclusion and Title IX Coordinator. Once SUNY Council issues the guidelines, Nolan-Weiss will meet with University Police and Student Life to ensure UB’s policies incorporate everything the new guidance requires. Many UB students are concerned with the policy changes.

“If we do make any changes, it’s likely to just be fine tuning things at this point,” Nolan-Weiss said. “Our offices work very closely to make sure we’re balancing everyone’s rights, handling sexual assault effectively and complying with whatever guidance is given to us.”

The new guidelines give universities the option of using “clear and convincing evidence,” a higher standard of proof, for sexual misconduct cases. The “Dear Colleague” letter required a lower standard of proof: “preponderance of evidence.”

UB uses the lower standard for all misconduct cases— not just sexual assault. This has always been UB’s policy, even prior to the “Dear Colleague” letter, according to Nolan-Weiss. Under this standard of evidence, the plaintiff needs to prove there is more than a 50 percent chance that the defendant is guilty, using both testimonial and physical evidence.

“So now they’re telling us we can still use that standard, or we have the option of using a higher standard, which is ‘clear and convincing evidence,’” Nolan-Weiss said. “So we are talking about a difference between, say, a 51 percent chance and a 75 percent chance.”

There is a possibility that the Department of Education could make the “clear and convincing evidence” standard mandatory, which would result in a change in UB policy, Nolan-Weiss explained.

Nolan-Weiss is concerned that the new guidelines are pushing a narrative that universities have gone “too far in the other direction” and making unfair accusations.

“You see a lot of language about kangaroo courts and that people aren’t allowed to speak about the hearing. That’s actually not our policy,” Nolan-Weiss said. “We desperately want to get these cases right, getting to a right answer, a fair answer.”

That means considering the evidence and weighing what both parties have to say, Nolan-Weiss said.

“We don’t want a victim of sexual assault to feel like their issue wasn’t addressed appropriately,” Nolan-Weiss said. “But we also don’t want to see someone who feels they were unfairly accused where there is not enough evidence charged with a violation that could end their academic career.”

Nolan-Weiss also expressed concern about interim measures. When someone reports a sexual assault or misconduct, there is a gap between the time they make the report and the time the hearing happens. Schools have always struggled with what to do in the meantime because the accused person could be a danger to the campus community, Nolan-Weiss said. But on the other hand, the accused individual is entitled to due process, she said.

“You don’t want to do something that is going to railroad their education if they’re not responsible for something,” Nolan-Weiss said.

The previous “Dear Colleague” letter supported universities taking action that might affect an accused student. The new mandate emphasizes the importance of looking at each case individually and making sure neither party’s education is interrupted, according to DeVos’ interim guidelines.

The “Dear Colleague” mandate also recommended the entire sexual misconduct judiciary process occurs in 60 days. The new guidelines relax this requirement, which Nolan-Weiss believes could be a good thing.

“Due to the complexity of these cases, it was often very challenging for us to have these done in 60 days,” she said.

Both parties have the option to bring an adviser, such as a parent, to their hearing, and the short time frame can make this difficult, according to Nolan-Weiss.

“You have to coordinate everybody’s schedules and sometimes we were kind of placed in a position to choose,” she said, “Do we want to force this to happen sooner and maybe tell somebody they can’t have someone present or do we want to extend it out and make sure everyone has their adviser in the room.”

Sophomore environmental design major Sophia Rogillio believes the extended time period elongates victims’ trauma, and also allows the perpetuator to potentially escape discipline. She is also concerned DeVos is trying to change Title IX rules in order to give power back to the perpetrators of sexual violence.

“Now the burden of proof is placed on the victim, who is already going through a lot of trauma and coping, all while trying to balance their other responsibilities,” Rogillio said.

She feels the “clear and convincing evidence” standard is “absurd” because often the only physical evidence a victim has is emotional trauma.

“Victims endure extreme emotional strain after events of sexual assault and rape, and rarely get rape kits,” Rogillio said.

Rape kits aren’t able to prove some types of sexual assault, Rogillio pointed out, such as digital penetration, oral sex and anal sex. Rape kits can be inaccurate, she said, especially if condoms were used or the women was menstruating.

“Even things like forced stripping and groping would be extremely hard to prove under DeVos' new rules,” Rogillio said. “The era of colleges sweeping sexual misconduct and assault under the rug has been a long battle, and [Devos’] new rules on handling these cases is reverting the hard work of victims and advocates trying to achieve justice.”

SA President Leslie Veloz is also disappointed with the proposed policy change.

“Not only will it make college campuses less safe but it sends a dangerous message to campuses to not believe its victims,” Veloz said. “Students will be discouraged from reporting assaults if they don't have ‘clear and convincing’ proof of their attack.”

Maddy Fowler is an assistant features editor and can be reached at maddy.fowler@ubspectrum.com