Kelley Mosher didn’t buy milk from a grocery store until she was 16 years old.

The senior environmental design and environmental studies major grew up on her family’s dairy farm in the southern tier of Western New York. Her father and grandfather ran the farm while her mother and grandmother took care of the garden. Because of her upbringing, she said she believes it’s important for students to know where their food comes from.

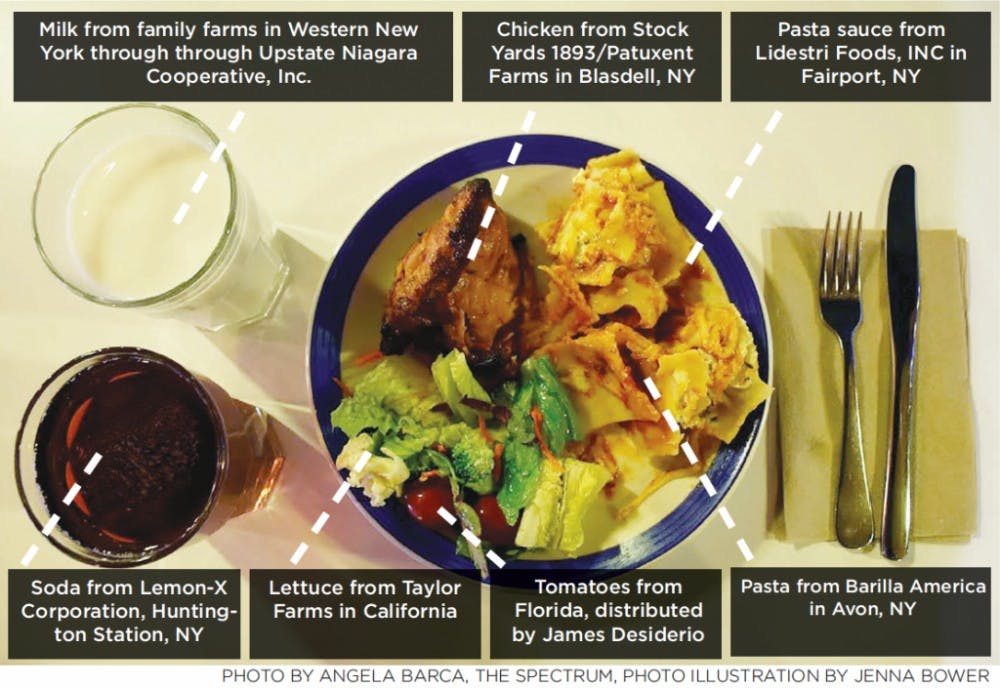

For students at UB, that means understanding the six-step process from various farms across the country to the roughly 30 on-campus eateries. In order to feed the 30,000 undergraduate and graduate mouths at UB, the university orders their food from both local farms and US Foods, a national company with access to 19 vendors nationwide.

UB gets 33-35 percent of its food from local vendors, totaling to around $3.9 million in local food purchases, according to the Campus Dining and Shops (CDS) website.

It’s nearly impossible for small local farms to supply enough products to sustain UB because of the amount of food the university requires, according to Samina Raja, an associate professor of urban and regional planning and the principle investigator of the Food Lab. For example, US Foods received 2,256 food and beverage orders from the university last November.

“It can be challenging for our dining services to buy from a farmer because the farmer cannot meet the demand that UB has,” she said. “There aren’t mechanisms where farmers can easily arrogate their supply for large institutions to buy and that’s not unusual in Western New York. That’s happening all across the United States.”

Because of this, UB orders most of its food through US Foods, a corporate company that has the ability to get food from vendors all over the country including lettuce from California, tomatoes from Florida and meat from Tennessee.

This means before a student can enjoy a slice from IncrediBull Pizza, CDS places an order with US Foods for 360 pounds of sausage meat. US Foods delivers 30 cases, on average, of sausage a week. The meat comes from Smithfield Farms in Tennessee and travels to Buffalo in one day. The meat is then inspected by Wardynski’s Meats, a Buffalo-based meat production company, and is delivered to UB.

Once on campus, UB’s chefs inspect the meat, ensuring it meets the school’s specific guidelines like safe levels of bacteria for human consumption and appropriate taste. Then it gets delivered to IncrediBull to be placed on a pepperoni slice of pizza, according to Dean O’Brien, the vice president of Wardynski’s Meats.

If the delivered food doesn’t meet UB’s standards, it is sent back to the vendor.

This process is the same for the other eateries on campus, some of which receive their food from different vendors.

Fowl Play, located in the Student Union’s Putnam’s eatery, served more than 18,200 pounds of chicken last year. In total, UB goes through 43,800 pounds of breaded chicken tenders in an academic year. That breaks down to 1,460 pounds per week and makes up, on average, 25 percent of UB’s monthly orders, according to Ray Kohl, the marketing manager of CDS.

Some students may not wonder how what they eat at UB gets to their plates. Not Mosher, whose experience on a dairy farm has shaped her life.

Mosher is working to educate students about where their food comes from. She is a student leader of UB’s Campus Garden, a student run organization partnered with CDS, which aims to educate students on the process of food systems. They use compost from Bulls’ football games and compost supplied by CDS to grow vegetables that will be used in the dining centers.

“The first real connection was knowing that what goes into the soil goes into my body and goes back into the environment and into the world,” Mosher said. “And as my love for the environment grew, I knew food was my heart song.”

She said many people only think about where their food comes from on a basic level but leave out the production process. Students take notice of the obvious: French fries come from potatoes and potatoes come from the ground. But the question of how those potatoes quickly turned into French fries doesn’t come to mind, she said.

Jeanne Leccese agrees. She’s an adjunct instructor and researcher in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning in the UB School of Architecture and Planning.

“It’s really easy to just go to the store and always know that there’s going to be food there and not think, ‘Where does this come from?’” she said.

In the fall, Leccese taught a class focusing on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus Green Commons, which is comprised of three historic buildings in downtown Buffalo that are being preserved and dedicated to alternative transportation, energy and food education.

When Leccese first presented the idea of building a food commons to her class, she was greeted with a roomful of blank stares. Many of her students wondered how food and environmental design are related. Some people, because of the way neighborhoods are laid out or due to a lack of transportation, don’t have access to fresh foods or grocery stores.

“Often times, the process of food distribution is invisible to consumers,” Leccese said. “As consumers, we see what’s in front of us in the grocery store and we don’t think about how far the food traveled or where it came from, only its accessibility.”

Mosher took Leccese’s studio class and is partaking in the Green Commons project. She said she believes her childhood experience living on a dairy farm contributed to her understanding of food distribution. She thinks every student should have a similar understanding.

“I think when you say the word ‘food systems’ to people, they don’t comprehend all the term encompasses,” Mosher said.

“Food systems” is the term used to describe the process food goes through before it lands on a plate, including growing, farming, processing, transporting and inspecting.

A challenge the food systems in the United States face is the prevalence of large corporations and their reach, said Raja, an associate professor of urban and regional planning.

This means large universities like UB and other institutions with a high demand for food are met with preventive barriers that don’t allow for direct communication with farmers. They’re always talking to big name distributers.

Erie County has taken notice, creating the Buffalo-Erie Food Policy Council, a subcommittee of Erie County’s Board of Health. The group works to improve local food systems and policies like making it possible for UB to buy from local farmers without being bound by a consolidated distributor.

There may be some disparity among students, but, overall, Raja said she’s noticed an increase of awareness surrounding food systems.

Students are now questioning, “How food gets from the farms to the tables and beyond” through a lens of their personal interaction with food in grocery stores coupled with what they’re studying in school, she said.

Mosher’s experience on her family’s farm makes her take pause when she’s buying food.

Not every student thinks about what’s on their plate, but Mosher and others hope they will.

email: news@ubspectrum.com