Iacchetta was home in Rochester. It was February 2011. The night before, she spoke with her beloved grandfather - her "Nonno" - on the phone. "I love you, bella," he told her.

Six days before her 18th birthday, Iacchetta lost her best friend when her grandfather died in the ocean; he suffered a heart attack.

A month later, Iacchetta had a compulsion. A need. She was about to discover a certain type of "itch" she didn't know she'd ever want to scratch as a way to cope with a loss she wasn't expecting.

Iacchetta found her answer under the needle.

"I felt like I needed him to be a part of me every second of every day," she said.

How many young people are getting tattoos is hard to quantify. Iacchetta thinks the number of college-age students getting ink is on the rise and artists agree. The Pew Research Center has reported 36 percent of 18- to 25-year-olds have tattoos.

Jess Rocha, a UB alum who owns RedHouse Tattoo in Depew, says she's seen statistics even higher.

"It's definitely a lot," Rocha said.

And with the increase in popularity, many students have an optimistic outlook - they believe the stigma commonly associated with tattoos is lessening. In 10 to 15 years, Rocha, who has been a tattoo artist for the last 15 years, expects the stigma to be mostly eliminated.

And though tattooed students have dealt with concerned - if not disapproving - parents and how the professional world may treat them, the prevailing sense of hopefulness about the future of tattoos is leading students to the needle's buzz.

"I think that our generation really gravitated toward tattoos because of the beauty behind it," Iacchetta said. "It is an art form and I don't think a lot of people understand that. They just think, Oh, these kids are being rebellious and want to get inked because they're 18 and don't know what they're doing."

Victoria Iacchetta has been getting tattoos since she was 18 years old. After the loss of her grandfather in 2011, she has been consistently drawn to ink.

Iacchetta never pegged herself as the tattoo type, but her memorial piece for her grandfather evoked a discovery of self-expression she never anticipated.

Since March 2011, Iacchetta, now a junior English and history major at UB, has accumulated eight tattoos, each with its own story. But the Italian flag on her foot with "Nonno" written over top will always be her favorite.

Iacchetta's body serves as somewhat of a roadmap of her life. Quotation marks are fixed on her wrists, a representation of the avid writer's love for the written word; "En attendant Godot," French for "Waiting for Godot," sits on her right forearm (she intends to one day read and understand the whole play in its original French); on her ankle in plain text is "explore." - which fits with not only her zest for history and other cultures, but her own exploration into tattoos. And that's naming fewer than half.

Iacchetta says in times of stress she has looked to tattoos as a type of therapy. Since she was 18, Lemma Al-Ghanem has turned to tattoos during times of transition. The 21-year-old architecture student - a former art student - has drawn each of her own tattoos.

Lemma Al-Ghanem has 12 tattoos. She's sketched out each one herself and likes to have her body art serve as a "bread crumb trail" that reminds her of her past.

It takes her longer than a moment to tell you just how many that is; she mentally works her way up from her feet to her hips, knees, wrists, ribs and even behind her left ear. The answer she settles on is 12 - that's within the last four years.

During visits to Syria - where her parents are from and her extended family still lives - she would get her body covered in henna. During one of those trips at age 13, she was seeking out a henna shop with her aunt when the pair landed in an actual tattoo shop, unbeknownst to her aunt. Al-Ghanem begged to get the type of body art that wouldn't wash off, but she would have to wait five more years.

When Al-Ghanem first started getting into tattoos, she'd carry around self-drawn sketches regularly - ready to alter her future tattoos the moment a new idea crept into her head.

Her first tattoo was an image of a keyhole on her wrist. She got it when she felt "locked into place," happily starting art school in her hometown near Washington, D.C. But her shoulder, which is the canvas to three floating leaves, tells a different story about transitions - a transition away from home and art school and to UB's School of Architecture.

She said her body art is "like a bread crumb trail." Each tattoo sits as an anchor (she does actually have an anchor on her hip), tying her to moments and feelings from her past.

"Nefs," an Arabic word on her wrist that means "self," prompts her to be true to what makes her happy. A bird is perched on her foot with the verb "to hunt" in Latin script, emphasizing the importance of going out and getting what one wants in life.

Like Iaccheta, Al-Ghanem understands the therapeutic facet of tattooing.

"It'd be different if it was just like sort of stamped on or right away put on ... seeing it spill onto my foot was really calming in a way," she said. "I was just like, 'I thought about this for, like, a year and I envisioned it,' but it's not until you actually see it creeping onto your body that you feel like it's kind of its own thing that's slowly integrating itself with you, which is a pretty cool, therapeutic feeling."

She gets a surge of adrenaline under the needle's steady sting; she views the feeling as a sort of tattoo adoption process, reinforcing the meaning she holds behind her pieces.

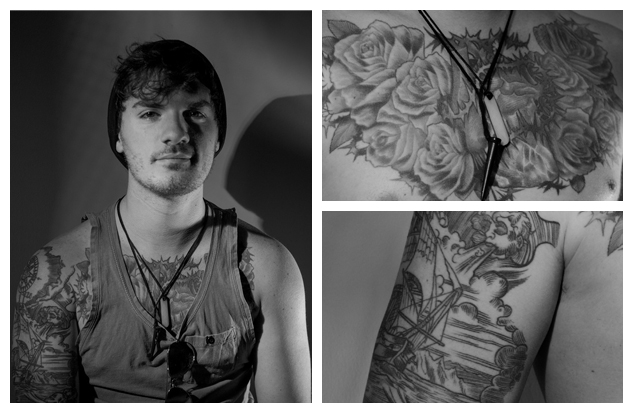

In addition to the stigma, pain also dissuades some from pursuing ink. But not Darrell Delaney, a senior English major, who has a sleeve and chest piece as well as hip and back tattoos.

"It hurt. I know it hurt," Delaney said. "You can remember how it feels like to jump in cold water or something like that, but I can't remember how it felt to have the needle digging in my skin."

Darrell Delaney first ventured into tattoos as an eager 15-year-old. To date, he's spent about $3,000 on his ink.

It's a pain that is hard to describe - sometimes adrenaline can help block the discomfort, but each person handles it differently. Iacchetta's foot tattoo gave her sweaty palms and the artist had to hold her body down because she was shaking.

Despite the pain, some people can't resist the urge to return to the chair for more.

Delaney's family jokingly calls him a "freak" whenever he takes his shirt off. Two days before Delaney's 16th birthday, his father took him to a shop to get a tattoo, likely not imagining his son's infatuation with the art form would eventually lead to aspirations to have much of his body covered in ink.

People with tattoos tend to talk about tattoos almost as if they were Lay's potato chips - it's difficult to have just one. They are easily taken over by "the itch."

An anatomical heart surrounded by roses is strewn across most of Delaney's chest; it blends almost seamlessly into a naval scene that takes up 3/4 of his right arm.

Delaney has spent about $3,000 on his tattoos and more than 24 hours in his artists' chairs. The 21-year-old sits at a different end of the tattoo scope from Iacchetta and Al-Ghanem; his tattoos don't have meaning behind them.

"There's two different ends of the spectrum," he said, comparing the way he uses tattoos to the way someone may choose the art to adorn their living space. "I just hang a painting in my apartment because it looks cool. And to me, my body is basically the ultimate canvas. It goes where I go. I don't have to invite people over to my apartment to see that 'cool painting;' they see it as soon as they meet me."

Regardless of Delaney's constant desire for more ink, he's conscious of where his tattoos sit.

Some people with tattoos joke about an "unemployment line" - a space, usually around the forearm or above the elbow, they won't go past out of fear it could affect their marketability in the professional world.

Iacchetta works at Tim Hortons and said she has been given no troubles for the pieces on her wrists and arms. Rocha is pleased to see employees at stores like Target and Wegmans with visible ink, piercings and dyed hair. She sees it as a symbol of progress.

Delaney's 3/4 sleeve allows him to roll up a dress shirt once without ink peeking out; his chest piece sits so he can unbutton the first button on a dress shirt without revealing what's underneath. He feels that individuals' perceptions of tattoos are improving, but he worries certain jobs may not be as accepting.

Al-Ghanem is frustrated she even has to consider the stigma; she knows some people view tattoos as "dirty." She has big plans - helping rebuild the $200 billion in damages to Syria big. She has lost four extended family members, most recently a cousin who was hit in the neck by shrapnel from a bomb, because of the country's ongoing conflict.

She wants to create a firm or company that will run on donations and help rebuild parts of the Middle East. But the idea that her greatest form of expression could potentially tamper with her life's biggest goal "messes with [her] head."

"I just don't want my company or firm ... to not get what it fully deserves because it's for other people," she said. "It's like a selfless thing, so I guess if I have to sacrifice not getting a full sleeve for that, I'm totally fine with that."

For the young and tattooed, parents' perceptions of ink seem to lean on the concerned side.

Iacchetta, who has never felt she's been treated any different by employers or professors due to her visible tattoos, did have to face her "traditional" and religious family. They didn't embrace her ink.

Though Al-Ghanem has a grandmother and aunt covered in tribal tattoos, her Syrian parents have trouble accepting her body modifications, viewing tattoos as an alteration of what God created and believing the family's previous generation didn't "know better." Al-Ghanem's father is only aware of her most visible tattoos.

"People need to understand the world is changing culturally and socially," Iacchetta said. Al-Ghanem described it as a "gradual climb."

And for those willing to go on that hike, Delaney has a few words of advice: always go to a professional and experienced artist. His venture into tattoos was more of an impatient leap.

At 16, Delaney got his first tattoo with his father's permission. It's a tribal tattoo that sits between his shoulder blades. At 17, Delaney wanted more tattoos. Too young to get one legally in a shop, he sought out what he described as a "basement tattoo." Delaney hadn't met the 'artist' - Rocha says people in the industry call these types "scratchers" - prior to getting the tattoo, which was put on with a homemade machine held together by rubber bands and hooked up to a makeshift battery.

The man who tattooed Delaney also took two breaks to smoke marijuana because he said it "made him work better."

"Long story short, don't get a basement tattoo," Delaney said. He has scar tissue and crooked lines on a design he assumed would be simple to execute.

Rocha said getting tattoos outside of a licensed shop leaves people at a huge risk of becoming exposed to infectious diseases from cross-contaminated needles.

Despite Delaney's cautionary tale, he doesn't regret any of his tattoos. Each denotes who he was at the time he got the piece - even the one he hates on his back. He uses them as a "timestamps" to show his own progression.

Tattoos have meanings that can be a struggle for some to articulate.

For Iacchetta, a gaze down at her foot brings back memories of lunch dates and soccer games with her grandfather.

"As much as people tell me that I don't need to get a tattoo in order for him to always be with me, I feel like my tattoo has done so much for me that nobody will understand."

All photos by Chad Cooper, The Spectrum.

Web design by Brian Keschinger, Ben Tarhan and Sara DiNatale.

email: sara.dinatale@ubspectrum.com